Veteran’s Day is observed on November 11 because 11/11/1918 is the day the Armistice was signed to end World War I. Twenty-seven Chicago Cubs (including six Hall of Famers) served during that War, and this is how they are described in the Eckhartz Press book EveryCubEver…

~Vic Aldridge 1893–1973 (1917-1924)

On the day President Harding died, the Cubs beat the Boston Braves 5-1 thanks to a great pitching performance by Vic Aldridge, the #2 starter on the team (behind Grover Alexander). Aldridge went on to win 16 games for the Cubs that year. It was in the middle of a very strong 3-year run with the Cubs, when he won 47 games. He was traded to the Pirates in 1925 in the trade that brought Charlie Grimm to the Cubs.

~Grover Cleveland Alexander 1887–1950 (Cubs 1918-1926)

His 373 wins are the third most in baseball history. And yes, he was a Cub. He won 128 games in his years with the Cubs, and had one of the best seasons in baseball history in 1920, when he led the league in wins, ERA and strikeouts. But Alexander was troubled during his Cubs years. The only reason they got him at all was because the owner of the Phillies didn’t want to get stuck paying the contract of his star pitcher (a three-time 30 game winner) if he got drafted into World War I. He did get drafted, and he came back from the war a changed man. Old Pete, as he was known, became one of the biggest drinkers in the league–during Prohibition. He showed up drunk to games. He fell asleep in the clubhouse and passed out drunk in the dugout. He smoked like a chimney before every game. He ignored his manager, and openly challenged his authority. The Cubs were understanding up to a point. After all, the man was suffering through medical, physical and mental problems. He was an epileptic, and was prone to seizures. His arm started hurting during his Cubs career, and he had the ligament “snapped back into place” by a man named James “Bonesetter” Smith. And throughout it all he was suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder after his horrific war experience. Somehow, against all odds, he continued to pitch well. In 1923, he pitched 305 innings and walked only 30 men. In 1924, he won his 300th game. But in 1926, after his catcher and best friend Bill Killefer went to the Cardinals, Alexander fell apart. In his last ten games with the Cubs, Old Pete showed up drunk six times, and missed two games altogether. The Cubs released him and the Cardinals picked him up on waivers. Back with his best friend Killefer, he regained his pitching touch and led the Cardinals to the World Series championship, winning Game 6, and saving Game 7 of the 1926 series. Two years after his 1950 death, his story was told in the film “The Winning Team,” starring Ronald Reagan. Grover Cleveland Alexander remains the only player in baseball history to be named after a president, and portrayed in a movie by a president.

~Sweetbread Bailey 1895–1939 (Cubs 1919-1921)

His real name is Abraham Lincoln Bailey because he shares a birthday with the famous president. What is the origin of his nickname? Well, “sweetbreads” is defined as “the thymus or, sometimes, the pancreas of a young animal (usually a calf or lamb) used for food,” and though the origins of Bailey’s nickname have been lost to time, historians think it may have come from Bailey’s tendency to swerve his pitches right into the batter’s “sweetbreads”. He hit seven batters there. The Cubs signed him in 1917, but before he joined the team he served in the military with the 72nd field artillery. He was a reliever for the Cubs, winning four games and saving none. That was the extent of his big league career. After a few more seasons in the minors, he returned to his hometown of Joliet, and that’s where he died of pituitary cancer in 1939 at the way too young age of 44.

~Bill Bradley 1878–1954 (Orphans 1899-1900)

Chicago signed him as a shortstop, but he made eight errors in his first five games, so they moved him over to 3B. When his career ended 14 years later, he was considered one of the top third basemen in baseball history. He jumped to the American League in a contract dispute in 1901 (urged to do so by another ex-Chicago star Clark Griffith), and over the next three seasons he was in the top ten in batting average, runs, hits, doubles, triples, homers and slugging percentage. He was also the best fielding third baseman in the league. How much was the difference between the Cubs offer in 1901 and the offer from Cleveland? $3100. Doesn’t sound like much, but it was 3/4 of his yearly salary.

~Jimmy “Scoops” Cooney 1894–1991 (Cubs 1926-1927)

Cooney was already 32 years old when he joined the Cubs in 1926, but he had only played parts of four major league seasons (two with the Cardinals, one each with the Red Sox and Giants). But the Cubs had no one else to play shortstop when they acquired him, so he was given the full-time job. During that 1926 season, he hit only .251, his on-base percentage was a woeful .288, and he had a whopping 24 extra base hits in more than 500 at bats. Still, his glove kept him in the lineup. The following season (1927) he was still the starting shortstop when that glove made major league history. On May 30, 1927, in the fourth inning of a game against the Pirates, Cooney caught Paul Waner’s liner, stepped on second to double Lloyd Waner, and tagged Clyde Barnhart coming down from first, to record an unassisted triple play. No other National Leaguer would do it for the next 65 years. In 1992, future Cub Mickey Morandini finally broke the streak by recording an unassisted triple play for the Philadelphia Phillies. How did the Cubs reward Cooney for his miraculous play? They traded him to the Pirates eight days later. (Photo: 1926 Baseball Card)

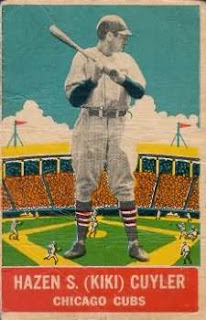

~Kiki Cuyler 1898–1950 (Cubs 1928-1935)

His real name is Hazen Shirley Cuyler. Cuyler was called “Cuy” by his school teammates. It was while winning the MVP title of the Southern Association with Nashville in 1923 that he acquired the Kiki nickname. Fans heard the players shout for him to take the ball when he rushed in on a short fly. The shortstop would yell, “Cuy,” and the second baseman would echo the call. In the pressbox the writers turned this into “Kiki.” (It’s the long “i” sound, although it doesn’t look like it.) Older fans wince when they hear him called “Keekee,” but they shouldn’t be too harsh on younger fans who have only seen this name associated with singer Kiki Dee. (That Kiki sang “Don’t Go Breaking My Heart” with Elton John and pronounced her name with the “e” sound). Kiki was a great player. He led the league in stolen bases four times, runs twice, doubles once, and had an incredible lifetime batting average of .321 (although he never won a batting title–he finished in the top ten five times). He was part of the Cubs pennant winners of 1929 and 1932, although his teammates didn’t like him much. They thought he was a bit of a fancy lad because he used to put suntan powder on his face. Kiki Cuyler was elected into the Hall of Fame by the veterans committee in 1968, eighteen years after his death. (Photo: 1933 Delong Baseball Card)

~Pickles Dillhoefer 1894–1922 (Cubs 1917)

His name was William Martin Dillhoefer, but everyone called him Pickles. During his rookie season in 1917 (his only season with the Cubs), he was the third string catcher behind Art Wilson and Rowdy Elliot. It’s safe to say that he wasn’t going to challenge Ty Cobb in the batters box. Pickles only batted .126 that year, and the Cubs finished 5th out of eight teams. Pickles was a throw-in to the trade that brought Grover Cleveland Alexander to the Cubs in 1918, and he played for the Phillies and Cardinals the next four seasons. His best year was probably 1920, when he batted a whopping .263 in 200+ at bats. Unfortunately, tragedy struck just as he was experiencing his greatest happiness. Pickles died at the young age of 27 from typhoid fever on February 23, 1922 just a few weeks after his wedding. He left behind a young bride, a colorful personality, and one of the best nicknames in baseball history. When the Sporting News did an article in 2001 about the best nicknames of all time, Pickles was named #1.

~Rowdy Elliot 1890–1934 (Cubs 1916-1918)

His real name was Harold Elliot, but his teammates called him Rowdy. The reason for his nickname has been lost to time, but when you hear Rowdy Elliot’s story, you can probably make an educated guess. He was a catcher for the Cubs from 1916 to 1918. His first year with the Cubs was the first year they played in what is now known as Wrigley Field. Rowdy was one of eight catchers to play for the Cubs that year. The 1916 group includes Nick Allen (four games), Jimmy Archer (61 games), Clem Clemens (nine), Rowdy Elliot (18), Bill Fischer (56), Bucky O’Connor (one), Bob O’Farrell (one) and Art Wilson (34). His Cubs career ended in May of 1918, when he suddenly left the team and enlisted in the Navy to fight in World War I. Rowdy played one more big league season after the war (with Brooklyn), and he bounced around in the minors after that. He played in the minors until 1929. Five years later Rowdy was dead. He fell from an apartment window and died from the injuries. Though the rumor was never confirmed, it’s been reported that Rowdy was drunk at the time of his death. A collection was taken up by friends to keep Rowdy Elliott, who was penniless, from being buried in a potter’s field.

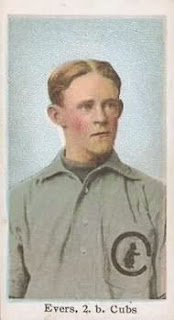

~Johnny Evers 1881–1947 (Cubs 1902-1913)

Johnny Evers was the starting second baseman for the greatest Cubs team of all-time, the 1906-1910 dynasty. He got his nickname, the Crab, for the way he sidled up to grounders, but he lived up to his nickname in another way. Evers was only 120 pounds, but he was known as tough and humorless. For instance, he didn’t talk to the other half of his double play combination, shortstop Joe Tinker, for many years. According to Evers, Tinkers started the fight in 1907 by throwing a ball too hard at Evers, breaking his finger. Then he laughed…which is of course, unforgivable. The two didn’t talk other than what they needed to say on the field, for over thirty years. First Baseman/Manager Frank Chance also didn’t like to listen to Evers’ constant bitching. He once considered moving him to the outfield just so he didn’t have to hear him in his one good ear. But Johnny Evers was a great fielder, a sparkplug on the offense, and despite his grumpy disposition, deserves his status as a member of baseball’s Hall of Fame. (Photo: 1910 Tobacco Baseball Card)

~Buck Freeman 1896–1953 (Cubs 1921-1922)

Freeman was part of the starting rotation of the Cubs in 1921 as a rookie, alongside the likes of Hall of Famer Grover Cleveland Alexander. Buck didn’t impress. He won 9 games, but he only struck out 42 batters in 177 innings. He got one more shot the following year and was hit hard. That was the end of his big league career.

~George Grantham 1900–1954 (Cubs 1923-1924)

In his two years as the Cubs starting 2B (1923, 1924), George led the league in strikeouts both years. He also led the league in being caught stealing. The Cubs traded him to the Pirates in the deal that brought Charlie Grimm to Chicago. Grantham had a good run in Pittsburgh. In his first season there he helped lead the team to a World Series title. He played with Pittsburgh for seven seasons before ending his career with the Reds and Giants.

~Burleigh Grimes 1893–1985 (Cubs 1932-1933)

Grimes never shaved on days he pitched, because the slippery elm he chewed to increase saliva irritated his skin, so he always had stubble on his face when he took the mound. That led to his nickname, Ol’ Stubblebeard. He wasn’t just known for his stubble, he was also known as one of the toughest competitors to ever take the mound. His scowl would have made Randy Johnson’s look like a smiley face, and when it was time to give someone an intentional walk, he was known to throw four pitches near the batter’s head. Grimes is a Hall of Famer, but certainly not for his one and half years with the Cubs (1932-33). He was a five-time 20-game winner, but only 9-17 for the Cubs. Ol’ Stubblebeard was the last legal spitball pitcher in the majors. When he retired, so did that pitch. (Wink, wink. Right, Gaylord Perry?)

~Percy Jones 1899–1979 (Cubs 1920-1928)

Percy was a fifth starter/spot starter for the Cubs during his time in Chicago. He had two double-digit win seasons (1926, 1928), but was included in the trade that brought Rogers Hornsby to the Cubs just before the Cubs made it to the World Series in 1929. One of Percy’s roommates with the Cubs was the hard-drinking Pat Malone. They didn’t get along. Jones insisted on getting a new roommate after Malone trapped some pigeons on a hotel ledge and put them in Jones’ bed as he slept.

~George High Pockets Kelly 1895–1984 (Cubs 1930)

Kelly was a member of the legendary 1930 Cubs team that blew the pennant in the last few days of the season. Tall for his time (6’4″), Kelly was nicknamed Highpockets and Long George by the press; but to his teammates he was Kell, a reserved and even-tempered Derrek Lee-type, and one of the best fielding first basemen of all time. He is a Hall of Famer, although not because of his years with the Cubs. Like many of the Hall of Famers who wore a Cubs uniform, he only wore it after he was washed up. He was in his 15th big league season. Kelly hit .331 in 39 games for the Cubs. He isn’t considered a Hall of Famer by many baseball experts, including Bill James, who calls him “the worst player in the Hall of Fame.” He was elected into the Hall by a veterans committee consisting of ex-teammates (with the Giants).

~Pete Kilduff 1893–1930 (Cubs 1917-1919)

Pete was an infielder (mainly second base) for the Cubs during the first few years at their new ballpark (Wrigley Field). He was on the pennant winning team of 1918, but didn’t appear in the World Series against the Red Sox. A few years later he got his only taste of the World Series as a part of the Brooklyn Robins. His claim to fame is being one of the three outs of an unassisted triple play. Pete was hired to be the manager of the minor league San Francisco Seals in 1930, but he died of an appendicitis attack before the season started. He was only 37 years old.

~Rube Kroh 1886–1944 (Cubs 1908-1910)

His real name was Floyd Kroh, but Rube was a common nickname in the first half of last century, indicating that the player was a country boy. Rube Kroh certainly fit that description. He grew up in a small town in New York named Friendship. Kroh’s first season with the Cubs was 1908, which was, needless to say, a very memorable year. He also played a bit part in the most important play of that season. He may have led the Cubs to the World Series without throwing a single pitch. It was a single punch that did the job. During the melee in the “Merkle Boner” game on September 23, 1908, while the Giants fans stormed the field before the umpire had called the game over, it was Rube Kroh that “forcibly retrieved” the ball from a Giants fan, and threw it in to Johnny Evers. Evers stepped on second base, and the Cubs won the game because the “winning run” didn’t count. Fred Merkle hadn’t yet stepped on second. The game ended in a tie, and the Cubs went on to win the pennant. Kroh also happened to be a good pitcher, but on that Cubs team, he wasn’t good enough to get on the mound very often. In three seasons during the Cubs dynasty years, he won 14 games. They let him go after the 1910 season. (Photo: 1909 Tobacco Card)

~Andy Lotshaw 1880–1953 (Cubs Trainer 1922-1952)

Andy was the Cubs trainer and also served in the same capacity for the Chicago Bears. Andy actually played an important role in the career of Cubs pitching great Guy Bush. Bush was one of the mainstays of the Cubs pitching staff during most of the 1920s and the early 1930s. He won double digit games in nine seasons in a row (including 20 wins one year), but was really best known for his incredible endurance. He was always among the league leaders in games pitched, and often served as the closer between his starts. During his Cubs years he pitched an amazing 2201 innings and completed 127 games. The rest of the league wanted to know what his secret was, but Guy Bush would never reveal it. There was a very good reason for that–he didn’t know what it was. Cubs trainer Andy Lotshaw applied a “secret dark liniment” to Guy’s arm, and Guy was convinced that liniment was what kept his arm loose. Andy wouldn’t even tell Guy what it was. It wasn’t until the Cubs traded Bush to the Pirates in 1935 that Lotshaw finally admitted the ingredients of the secret dark liniment to the pitcher. It was Coca-Cola.

~Pat Malone 1902–1943 (Cubs 1928-1934)

Malone was a two-time 20-game winner with the Cubs and led the team to the 1929 and 1932 World Series, but he also hung out with Hack Wilson. When they weren’t playing baseball, they were either drinking or brawling. The stories are legendary. In Malone’s first season with the Cubs his roommate was Percy Jones. They didn’t get along. Jones insisted on getting a new roommate after Malone trapped some pigeons on a hotel ledge and put them in Jones’ bed as he slept. One night Malone and Wilson got into a huge fist fight in a hotel. They were walking down the hallway of their hotel, and Wilson laughed. Someone in a hotel room mimicked his laugh. Wilson and Malone broke into the room and beat the hell out of four men, until all of them were out cold. One of the men was still standing and Malone kept punching. Wilson pointed out that he was already knocked out. “Move the lamp and he’ll fall.” Malone moved the lamp, and the man fell to the ground. It didn’t end well for either man. Wilson was only 48 years old when he drank himself to death. Malone didn’t even last as long as Hack. He was only 40 years old when he died in 1943. (Photo: 1934 Goudy Baseball Card)

~Rabbit Maranville 1891–1954 (Cubs 1925)

Nicknamed for his speed and rabbit-like leaps, Rabbit Maranville was always a great fielder, but he was even better known for his partying. One time when he was on the Pirates, there was a ‘no drinking’ rule on the team (which was understandable considering it was against the law at the time). A teammate, Moses Yellowhorse, wouldn’t pitch unless he got something to drink. Maranville summoned the infield around, pulled a flask out of his pocket, and gave the pitcher a snort. He once took a pair of glasses out of his pocket, polished them, and handed them to an umpire. Another time (with the Cubs in spring training 1925) he was goofing around on the golf course with Charlie Grimm, who laid on his back and put a tee in his mouth with a ball on it, as a joke. Maranville hit the ball with a driver, scaring the hell out of Grimm. Another time he dove into a fishpond at the Buckingham hotel in St. Louis, and came out of the water with a goldfish in his mouth. Once when he was in New York, he arranged for pitcher Jack Scott to chase him through Times Square shouting”Stop Thief!” Another time his teammates heard wild noises coming from within his locked hotel room; screams, gunfire, breaking glass…..the Rabbit moaning “Eddie, your killing me!” It sounded like a murder in progress! When the door was finally broken down, the Rabbit and two accomplices paraded right by his shocked teammates as if nothing happened, with the Rabbit greeting them with a “Hiya fellas!” The first night after he became Cubs manager, he barged into the players Pullman cars and threw cold water on their faces, saying “there will be no sleeping under Maranville management”. That same night he got into a fight with a cab driver in New York after the Cubs arrived there over the cabbie grumbling about his tip. He had to be separated from the cabbie by the cops. After they separated him, he went after the cops and was arrested along with two of his players. He had no set rules for the team except that they couldn’t go to bed before him. Another time he held the Cubs traveling secretary out of a hotel window by his feet. Yet another time, and as it turns out, the final incident, he ran through the train throwing the contents of a spittoon at his players. With Rabbit as manager, the Cubs finished in last place for the first time in franchise history. He was fired after eight weeks. Rabbit played for another ten years (with Brooklyn, St. Louis and Boston), and was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 1954. His real name was Walter.

~Johnny O’Connor 1891–1982 (Cubs 1916)

If his name sounds Irish, there’s a good reason for that. Johnny O’Connor was born in Ireland. He came to America and attended the University of Illinois. The catcher got one shot in the big leagues, and it wasn’t on offense. He came in as a defensive replacement on September 16, 1916, but was replaced by Art Wilson before he got a chance to bat. The game was in Philadelphia, and the Cubs lost to Grover Cleveland Alexander (his 29th win of the season) and the Phillies, 6-3.

~Elmer Ponder 1893–1974 (Cubs 1921)

Ponder was a pitcher for the 1921 Cubs. The righthander didn’t miss many bats. He gave up 117 hits and 7 homers in only 89 innings. He was part of the package of players the Cubs gave up to get Jigger Stats. Ponder never pitched in the big leagues again.

~Lance Richbourg 1897–1975 (Cubs 1932)

Richbourg (photo) was a backup outfielder on the 1932 pennant winning Cubs. It was the last season of his eight-year big league career (spent mostly in Boston). He was 34 years old at the time, and backed up all three starting outfielders: Kiki Cuyler, Johnny Moore and Riggs Stephenson.

~Dutch Ruether 1893–1970 (Cubs 1917)

He was just a rookie pitcher when the Cubs sold him to the Reds. How could they have known that he would go on to win over 130 major league games (three seasons were great 21, 19, and 18 wins), and lead two teams to the World Series (1919 Reds and 1926 Yankees). He won a game in the 1919 World Series for the Reds, but then again, the White Sox threw that series. After his playing career ended, Dutch came back to the Cubs and worked for them as a scout. Among the players he signed; Peanuts Lowrey and Joey Amalfitano.

~Vic Saier 1891–1967 (Cubs 1911-1917)

Vic was one of the players who played in the last season at West Side Grounds, and the Cubs’ first season at Wrigley. The first baseman had huge shoes to fill on the Cubs–he replaced the Peerless Leader, Frank Chance. When he was healthy, Saier was a beast–a combination of speed, power, and clutch hitting. In 1913 he hit 21 triples, drove in 92 runs, stole 26 bases, and hit .289. He hit a career high 18 dingers the following season, and had another solid year in 1915. But that season he suffered a bad leg injury, and Vic was never the same. The injury robbed him of his speed–a key ingredient of his game. Saier was done by 1919 at the age of 28.

~Johnny Schulte 1896–1978 (Cubs 1929)

Not to be confused with superstar outfielder Wildfre Schulte (no relation), this Schulte was a backup catcher for the Cubs (and the Browns, Cardinals, Phillies, and Braves). His one season in Chicago just happened to be a pennant winning year, although Johnny didn’t get to play in the World Series against the A’s. After his playing career he became a coach, and was on the staff of many World Series champions with the Yankees. He also worked as a scout for ten years. (Photo: 1933 Goudy Baseball Card)

~Pete Scott 1897–1953 (Cubs 1926-1927)

He was a part-time first baseman/outfielder for the Cubs for two seasons, but he paid huge dividends for them. Scott and teammate Sparky Adams were traded to the Pirates for future Hall of Famer Kiki Cuyler.

~Earl Smith 1891–1943 (Cubs 1916)

He got his cup of coffee with the Cubs in their first season at their current ballpark. During that 1916 season, the corner outfielder got only twenty-seven at-bats, all of them in the month of September. He did manage seven hits, including a double and a triple, but the Cubs released the 25-year-old after the season. He later resurfaced with the Browns and the Senators.

~Pete Turgeon 1897–1977 (Cubs 1923)

He played for the Cubs at the very end of the 1923 season and managed to get into three games and get six at bats. Four of those at bats came in the final game of the season when he started at shortstop for the Cubs. He got a single and scored a run in 6-3 loss to the Cardinals. He was back in the minors the following year and never made it back up for another taste of the show.