Sad news. Christopher Plummer has passed away at the age of 91. He will always be Captain Von Trapp to me.

Musings, observations, and written works from the publisher of Eckhartz Press, the media critic for the Illinois Entertainer, co-host of Minutia Men, Minutia Men Celebrity Interview and Free Kicks, and the author of "The Loop Files", "Back in the D.D.R", "EveryCubEver", "The Living Wills", "$everance," "Father Knows Nothing," "The Radio Producer's Handbook," "Records Truly Is My Middle Name", and "Gruen Weiss Vor".

Friday, February 05, 2021

Free Kicks

This week's episode includes a lively discussion about the many American soccer players now playing overseas. https://t.co/e366wWcdCd

— Rick Kaempfer (@RickKaempfer) February 5, 2021

Thursday, February 04, 2021

Minutia Men Celebrity Interview--Loverboy lead singer Mike Reno

This week's interview subject is #Loverboy lead singer Mike Reno. Would you believe he does a pretty passable Dudley Do-Right impersonation? https://t.co/5PYOOSKiqb

— Rick Kaempfer (@RickKaempfer) February 4, 2021

Wednesday, February 03, 2021

RIP Wayne Terwilliger

At the time of his death he was the oldest living Cub. That title now passes to Bobby Shantz, who pitched for the Cubs in the last season of his career (1964) after being a throw-in by the Cardinals in the Lou Brock trade. #Cubs #everycubever https://t.co/ci641XIZXe https://t.co/shg7HbfbIZ

— Rick Kaempfer (@RickKaempfer) February 3, 2021

His entry in EveryCubEver...

~ Wayne Terwilliger 1925-- (Cubs

1949-1951)

Twig, as he was known by his teammates, made his big-league debut for the Cubs on August 6, 1949. He made enough of an impression on the team to earn the starting second base job in 1950. He hit 10 homers for them that year. The following season he was traded to Brooklyn along with Andy Pafko, Johnny Schmitz, and Rube Walker in one of the worst trades in Cubs history. Twig later also played for the Senators, Athletics, and Giants. On the day this issue of EveryCubEver was sent to the printer (10/20/20), Wayne was the oldest living Cub.

The Day the Music Died

On the Eckhartz Press "Studio Walls" blog today...

On February 3, 1959, a plane crash claimed the life of rock and roll stars Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and the Big Bopper. Over the years, Eckhartz Press co-publisher Rick Kaempfer has interviewed several people about that day, including the MC of that last concert (DJ Bob Hale), one of the Crickets (Niki Sullivan), and the man who analyzed the famous song written about that day “American Pie” (DJ Bob Dearborn). Here a few highlights to help you better understand the impact of Buddy Holly on rock and roll, and his death on America…

Rick: I know you’ve had to answer this question a million times, but please indulge us by answering it one more time. You were the Master of Ceremonies on February 2, 1959 in Clear Lake, Iowa–the last concert by Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and the Big Bopper. Describe the scene backstage for us, and explain your part in that ill-fated coin-flip.

Bob Hale: The bus with Valens, Holly, Richardson, Dion, and Frankie Sardo arrived in the late afternoon…actually around 6PM . We hurriedly got them something to eat, and then all pitched in to set up for the performance. Those days were pre-high-fi days, so we had to deal with only one microphone. The tour manager was Sam Geller of the GAC Corporation (which would go on to purchase Ringling Brothers, Barnum and Bailey Circus). As the set-up was taking place, Buddy was playing the piano. Sam and I were listening and he said to me, “This guy is going to be one of the greatest popular music composers of our time. He’s so talented – he can play so many instruments, and he creates such interesting music.”

Buddy’s talents were put to use during the concert as he played the drums during the Dion set. The regular drummer, Charlie Bunch was in the hospital in Green Bay , Wisconsin , having suffered frostbite on the broken down bus! Buddy would play the drums for Dion’s set, which began the second half of the show. The first half was Frankie Sardo, and Big Bopper.

The second half, Dion and the Belmonts, followed by Buddy.

When Dion’s set was over, I sat down with him on the riser in front of the drum set and asked him to introduce his musicians. (Photo: Dion & The Belmonts 1959) When it came time for the drummer Dion said something like: “This fellow is taking the place of Charlie Bunch, our regular drummer who is in the hospital in Green Bay suffering from frost bite. Um…let’s see…the drummer’s name…is…ah, oh yeah! BUDDY HOLLY!”

Buddy jumped up, grabbed his guitar and began singing “Gotta Travel On.” The backup men quickly changed places and joined Buddy before he was half way through the first stanza.

There was some drama taking place off-stage, even before we got started, actually. At one point Bopper (photo) was sitting with my wife, Kathy, and me in a booth. Kathy was expecting our first child, and Bopper said something like, “That’s what I miss most…being around my wife when the baby moves. Kathy, may I feel your baby moving?” Kathy took Bopper’s hand and placed it on her stomach as the baby moved. Bopper smiled: “I can’t wait to get home to do that.”

Interestingly, no such conversation took place involving Buddy. We didn’t even know at that point that Maria was expecting.

During intermission the back-and-forth conversation between Bopper and Waylon Jennings took place, resulting in Waylon giving up his seat to Bopper. At that point Waylon uttered a phrase that would haunt him all his life – “Well, OKAY, but I hope your plane crashes!”

Years later, at a social gathering in Kentucky, Waylon (photo) and I recalled that night. He said: “Man, there isn’t a day goes by that I don’t wish I could take back that comment. The next day when I got the news in Fargo, I went nuts. I cried, I yelled. And I began to drink. Drugs helped along the way. Of course, I realized years down the road I was killing myself, so I quit. I don’t know, maybe deep inside I was so damned guilty, I was trying to kill myself!” He admitted that no matter how long he’d live, he’d always be haunted by Feb 3rd 1959.

After the show was over that night, Tommy Allsup, pressured by Ritchie Valens, said, “Let’s flip a coin.” It’s at this point that two versions of the coin flip emerge. Tommy maintains he flipped the coin; I maintain that as soon as he suggested it, he reached into his pocket and realized he had no money – he was still in his stage clothes. He asked me if I had a coin. I took out a 50 cent piece, said to Ritchie, “OKAY, Ritchie, you want to go, you call it.”

“Heads!”

“Heads it is, Ritchie, you’re flying.”

Tommy said, “OKAY,” and went out to the car to retrieve his bags which he’d already put in Carroll Anderson’s car. Regardless which version of the coin toss you hear or accept neither Tommy nor I demand “ownership.” We’ve talked about this, and have no emotional investment in either version. What we agree on is that night was a tragedy and an extremely emotional one for us all.

Rick: What was that next day like?

Bob: February 3rd would be a painful day for family, friends, fellow-musicians, and for those who attended the Winter Dance Party. Within minutes of my announcing the plane crash – I was pulling the 9 to noon shift on the 3rd, teens began arriving at the station (KRIB) just to talk. It became a day-long wake, Pepsi and Coke distributors brought extra cases to our studios – we had so many people just “hanging around.” Parents came, too. Many had been at the Surf the night before. It was the custom of Carroll Anderson to invite parents to the weekly record hops free of charge. Many teens and parents were in tears.

Some students from Waldorf College had been at the Surf the night before. Some came to the studios. I interviewed college as well as high school students. What I didn’t know at the time was that Waldorf, a two-year Lutheran college, did not condone dancing! The school had a rigid Danish-Lutheran background which was extremely conservative in social activities – “Sad Danes,” they were called in Lutheran circles. When the school heard about the students who’d been to the Surf, they immediately suspended the dozen or so students for a couple of weeks. No comments on the deaths – just on “school policy.” Fortunately time has given Waldorf a more enlightened school administration, as well as transforming the college into a four-year, well respected liberal arts college.

On the way home in the afternoon, after conducting about two-dozen telephone interviews with radio stations across the country, I drove by the crash site. The bodies had still not been removed, as the ambulances were still in the corn field. I could not bring myself to walk the hundred yards to the site – and to this day, I’ve not been able to make that walk!

Niki Sullivan was in Buddy Holly’s band. He appeared on the John Landecker show when Rick was the producer (in the 1990s). This is the article Rick wrote about that interview…

Among the people who joined us on the John Landecker Show over the years was the original guitarist of the Crickets, Niki Sullivan. He came to Chicago in the 90s as part of The Buddy Holly Story stage show. He was kind enough to get up real early one morning while he was in town to spend the better part of an hour on the John Landecker show.

We could have listened to Niki’s stories all day long. One of my favorite stories, because it involves two of the biggest stars in rock and roll history, was the story about the day Elvis Presley came to Lubbock, Texas. Buddy had won a contest as the best vocalist in Lubbock, and the prize was performing as opening act for Elvis. Niki was there that day too, and described what happened.

“Boy, Buddy was excited. You have to understand, it was 1955, and Buddy was already pretty well known in the Lubbock area at the time, but just hadn’t been able to break through nationally. Well since he was the opening act, he had access to the backstage area, and he approached Elvis—who had a couple of hit songs at the time–and asked Elvis if he had any advice. Elvis said sure, and invited Buddy into his dressing room. Well, he and Elvis went into that dressin’ room, and when Buddy came out a few minutes later—he was a different person. We asked him what they talked about, but he wouldn’t say. He just smiled. Whatever it was, and he never did tell us, after that night he was even more driven to succeed. It wasn’t too long after that he did.”

Niki was there for the recording of Buddy’s first big hit: “That’ll be the day.” He toured with the band the whole year of 1957, including a famous show at the Apollo Theatre. The black audience there that night had no idea what to think when they saw this group of good ol’ white boys, but the band won them over. It was a critical moment in Buddy Holly’s career, and was

featured in the movie The Buddy Holly Story starring Gary Busey. Unfortunately for Niki, it wasn’t portrayed accurately in the film because it shows only three men on stage that night. The Cricket they omitted was Niki Sullivan.

“It’s because I didn’t talk to the guy who wrote the first biography of Buddy. I was at the hospital because my kids were being born, so I wasn’t around when he came to town. Well, sure enough, when that book came out, I wasn’t a part of the story anymore.”

Sullivan was still part of the Crickets when they performed “Peggy Sue” on the Ed Sullivan Show. He told us what happened when Sullivan met Sullivan.

“He talked to Buddy before the song, but then during ‘Peggy Sue’, I heard him yell ‘Hey, Texas boy, do it!’ So I did a little dance. If you ever see that performance, watch the reaction of our bass player Joe.”

I never saw that performance until I listened back to the tape of our interview to write this column. In the 90s when we talked to Niki, YouTube didn’t exist, and it wasn’t so easy to track down some of that old TV video. Now you can, and here it is.

Niki Sullivan left the group just a few weeks after this performance in December of 1957, because he couldn’t take the rigors of touring anymore, and he wanted to be home with his family. He wasn’t part of the band for their biggest year of 1958, and he wasn’t part of Buddy’s tour in 1959. That turned out to be a lucky break.

“But I’ll still never forget that day,” he told us, his voice still choking up nearly forty years later. “I’ll never forget it.”

Niki Sullivan died in his sleep in 2004, 45 years after his good friend Buddy Holly perished in that Clear Lake Iowa cornfield.

Bob Dearborn was a DJ at WCFL-Chicago in the 1970s and became famous for his analysis of the Don McLean song “American Pie”, a song that McLean refused to explain. Bob was also a huge Buddy Holly fan. On the anniversary of the crash (back in 2006), Rick asked Bob to write a piece explaining what that day meant to him. Here it is, reprinted for you today, 15 years after Bob wrote it…

Some dates – December 7, 1941; November 22, 1963; August 16, 1977; September 11, 2001 – remain as indelible in our minds as our memory of the shocking events that took place on those dates.

We have just marked the anniversary of another stunning tragedy, one not as big as those others but an important milestone for many people of my generation and, to be sure, for me personally: 47 years ago, three popular young music stars perished on what came to be called a dozen years later, “The Day The Music Died.”

In the very early hours of February 3, 1959, a small plane chartered after a concert in Clear Lake, Iowa, crashed shortly after takeoff leaving all four on board dead: the pilot, singer Ritchie Valens (‘La Bamba,’ ‘Donna’), J.P. Richardson who performed under the name, “The Big Bopper” (‘Chantilly Lace’), and Charles Hardin Holley, known by millions of his fans the world over as Buddy Holly.

I had seen death before, close up, although the earlier experience for me was more curious than catastrophic, more surreal than sad. Oh, I liked my grandparents, all right, but I was 10 and 11 years of age when they died and I hadn’t developed enough yet intellectually or emotionally to really understand or feel an impact of their passing.

Of course, two years later, I was much more mature, and starting to realize all kinds of important things. What a revelation it was to discover that music could be about more than the beat, that movies and TV shows could be more than shoot ‘em ups and car chases, that the sudden loss and finality of death could be devastatingly sad.

The first time I was really moved by the passing of someone I cared about was when Buddy Holly died – somebody I “knew” only from his music, his hit records, his appearances on “The Ed Sullivan Show.”

I couldn’t have guessed it at the time that his music would have a great influence on future generations of musicians and songwriters, including the young, not-yet-famous Beatles and Rolling Stones. I just knew I liked it. From “Peggy Sue” and “That’ll Be The Day” through everything that followed, I was first a fan of his music.

He changed the style of rock ‘n’ roll music by altering the chorus and verse pattern of contemporary song composition. He popularized the four-man group configuration. Buddy was the one who advised Elvis to get a drummer (to join Scotty and Bill in Elvis’ backup band). He was the first rock ‘n’ roll singer to use violins, a whole string section, on his records (‘It Doesn’t Matter Anymore’). For a man who enjoyed fame for only the last year and a half of his young life, he made the most of it. Leaving his fingerprints all over contemporary music, his influence has been felt and his popularity has sustained for almost 50 years.

It was more than the music for me, however. In an era of pretty-boy teenage idols ruling the music charts, here was this young Texan who was kinda … geeky. He wore horn-rimmed glasses on his face and his emotions on his sleeve for all to see and hear – from the youthful pedal-to-the-metal exuberance of songs like “Rave On” and “Oh, Boy!” to the playful intimacy of a song like “Heartbeat.”

This guy was not only different and good, he was the first rock ‘n’ roll star that I could relate to, since I was a gawky, sensitive, geeky kid with black, horn-rimmed glasses, too! Buddy Holly’s acclaim and success confirmed that it was okay to be and look that way, that I was okay. He was MY hero. And his death was a crushing blow.

Ritchie, the Bopper and Buddy were the first popular music/rock ‘n’ roll heroes to die suddenly, shockingly at a young age. Theirs are the first names on a list that we review with heartache for its scope and length: Eddie, Johnny and Jesse … Patsy, Gentleman Jim … Sam, Otis and Frankie … Janis, Jim, Jimi, Ronnie and Duane … Jim, Rick, Karen, John, Harry … Marvin and Stevie Ray. Elvis. John.

Each time the bell has tolled, we’ve been stunned to learn of the loss of another hero, another artist who touched us with their music, a person we never met but who was so much a part of our lives that we viewed them as friends. And, too, with each passage, we’ve felt the loss of yet another important touchstone of our youth.

For me that all started with Buddy Holly. I was changed by his presence while he was alive, profoundly moved by his untimely death, always transformed by his music. And touched yet again by all of that in late 1971 when I first heard Don McLean’s brilliant composition, “American Pie.” Masterpiece is not a big enough word to describe that recording.

The song’s story begins with Buddy Holly’s death … as felt and told by one of his great fans, Don McLean. The clever metaphors of American Pie’s lyrics, then as now, leave many people confused, unable to understand what the song is about. Don and I are the same age, we lived through the same music era with similar reactions to all the changes that occurred, and we were, first and foremost, big Buddy Holly fans. I knew immediately what Don was saying in that song.

Where did all this lead? I invite you to click on the link below that’ll take you to a Web site that Jeff Roteman created in tribute to my analysis of American Pie. I hope you enjoy “the rest of the story” at this site, that it helps you appreciate what a wonderful piece of work American Pie is, that it makes you want to know more about Buddy Holly and his music, and that you find the experience a fitting observation for the 47th anniversary of “The Day The Music Died.”

When the Lawyers have Prepped you for an Interview

Newsmax invites Mike Lindell, who advocated for a coup and spews dangerous conspiracy theories, on air. It didn't go well. pic.twitter.com/6xzSgXlHua

— Jason Campbell (@JasonSCampbell) February 2, 2021

Tuesday, February 02, 2021

Big Bang

Monday, February 01, 2021

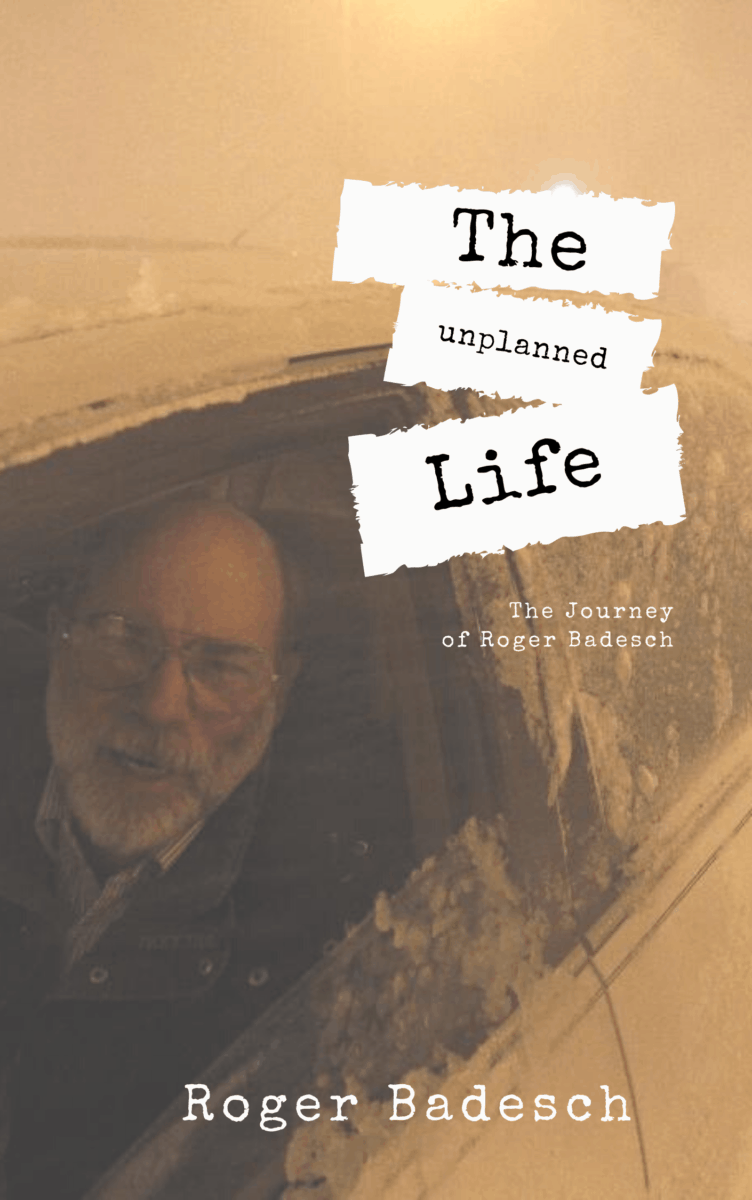

Free Excerpt: The Unplanned Life

On February 1, 2011, Chicago was hit with a horrible snowstorm. Eckhartz Press author Roger Badesch was caught in the storm in a way that would forever make him famous. It inspired the cover of his book The Unplanned Life. Today we present that portion of his book as a free excerpt.

The great blizzard of 2011 along Chicago’s lakefront was the event that legends are made of. A moment that many WGN Radio listeners can remember where they were when they heard of my exploits trapped in my car on Lake Shore Drive.

This is the true story:

For a couple of days before the event, I knew of the coming storm. There was hope among the staff at the school that school would be let out early. On the day of the blizzard less than 50% of students showed up and nearly all were gone by noon.

CPS did not release the staff early, though some teachers bolted by 1:00 p.m. either knowing their students were all gone or had worked out a deal with other adults in the building to cover their classes and punch out for them.

Being the conscientious teacher that I was, I stayed through the end of school at 2:45 p.m. along with the handful of my students who stayed because 1) they live close to the school and weren’t worried about the storm, or 2) they were too scared of my grading system to not show up and lose their class points for the day.

I kept checking the websites to see where the storm front was and how traffic was moving. When I left my classroom at 2:45 p.m. I had calculated that if all went well I could get home before the bulk of the storm made a mess of things.

Yes, I had heard all of the warnings about staying off the drive. Yes, I knew I was taking a chance. My thinking was that it was my shortest distance to get home as opposed to heading over to the Dan Ryan and trying to make it up to Touhy Avenue on the Edens—a longer drive and more cars to deal with. I also knew that the focus, should things become unmanageable for the city, would be on the main roads including Lake Shore Drive and, should I become stuck there, rescue would be forthcoming.

As it turned out, it didn’t matter if I had gone to the Dan Ryan, stayed on Lake Shore Drive, or taken Western Avenue or some other main north-south route. Traffic was screwed up all over.

As I was walking towards the main office to clock out, Jerral Stringer, one of my colleagues, was leaving his classroom and asked if I could give him a ride home. I’d often given him a lift as he lives on my way.

I headed out to Jeffrey Avenue and drove north to where it merges into Lake Shore Drive. The flow of traffic wasn’t bad and the roads were still easily passable. We quickly made our way up to Roosevelt Road and got stopped by the traffic light.

By now, traffic on the Drive had increased as more and more people had gotten out of work early and were trying to get home. While the city had issued warnings during the day, there was no city presence on the Drive—no plows, no police, no tow trucks, no nothing.

At Roosevelt, I contemplated for a minute pulling onto Roosevelt and trying to head west to the Dan Ryan, hearing on the radio that there was less precipitation there than there was along the lakefront. But then I heard that traffic on the Ryan and Edens was just as crowded as it was on the Drive, so I stayed on the Drive when the light turned green.

I moved smoothly between lanes and cars, trying to anticipate drivers who would cause traffic to stop and get stuck. I made it past the stalled CTA bus near Fullerton, weaving through the lanes, picking my spots, and my speed was at least 30 miles an hour.

I’d heard that traffic was starting to build because of a jackknifed CTA articulated bus on the exit ramp at Belmont and kept my eyes open hoping we could get through. As we passed Fullerton and continued toward Belmont, the intensity of the storm increased at least 20-fold. It was no longer just heavy snow, it was now windblown snow and ice off the lake, which was a mere 200 or so feet along my right side as I continued northbound.

I could barely see ahead but was anticipating that traffic would be stalled along the right lane of the Drive waiting to get off at Belmont. And I was right. I kept moving to the left inner lane, still moving along at a decent 15 miles an hour or so.

I was right about the traffic in the right lane. What I didn’t anticipate were drivers who had waited until the last second to move left to get around the stalls and then getting stuck themselves behind the car on their right who was stalled. This effect turned into what I’ve described in the past as a ‘snake’ winding its way from the right lane to the inner left lane.

As I approached, I saw what I thought was a space wide enough to get through along the inner left lane, using the extra couple of feet between the lane marker and the island divider as my last resort. But I had to slow to a crawl to make sure I didn’t clip the car that had stalled to my right.

I truly believed then and still do today that had I not been forced to slow down like that, I could have made it through the space on the left, moved over to the right, and made it through that Belmont curve of the drive and gotten past the worst of the storm.

It was right there at the curve that the winds were the strongest coming from the north-northeast off the lake—50-mile-per-hour winds pulling moisture from the lake and slamming ice bullets into the cars, combining with the snow falling at a record rate.

But it wasn’t to be. Jerral and I sat there in the car, heater warming us, phone charging on the cable plugged into the cigarette lighter outlet. Not moving. We could hear the wind. We could hear the crackling of the ice bullets hitting the car.

I was quietly angry at myself for having gotten that far in a tremendous feat of driving and getting stuck at the last second. At first, we were content with just sitting there and waiting things out. I had at least a half tank of gas and knew that the mayor would not let a repeat of the blizzard of 1979 happened again.

I was wrong. The clearing of Lake Shore Drive after the sun went down was a disaster by the city. I remember looking at the nearly clear southbound lanes of Lake Shore Drive as a phalanx of city snow plows came roaring past us headed the wrong way.

Sometime later, Chicago police officers on snowmobiles rode through asking if everyone was alright and to just hang in there. A short time after that, a CTA bus came in the southbound lanes and picked up people who didn’t want to stay in their cars. At this time I thought we were still okay and would eventually be plowed out and make our way home.

As the evening went on and I was listening to WGN Radio, I was also checking my emails on my phone and noticed one from a producer at WGN TV asking if anyone knew anyone who was stuck on the drive. For some reason, after getting stuck, I had not thought of filing any stories—only of trying to get home.

I decided to respond and the producer asked me to call in, which I did. I then decided, like a true journalist (or a completely brain-dead driver), to do a “scene setter” report for WGN Radio.

I stepped out of the car (now knee-deep in snow, with my too-thin winter jacket on and no boots on my shoes), and called the newsroom and filed a report. My jacket was coated in ice. My feet starting to freeze up. It wouldn’t be the last time I stepped out of the safety of the car to file reports for the station that night before my phone battery died.

Sometime after that, we noticed a handful of people walk past us towards Belmont—either bus passengers or car drivers or both. And not long after they passed us, we saw them walking back—the snow too deep to get through.

We also saw a group of men who either came from the Belmont area or from other cars who walked up to the line of cars in front of ours and started to help push those cars out of the drifts and helping them get back on the road north.

I could see enough ahead of us to see the outline of an articulated earth-mover for a few minutes and then watching it disappear, not to be seen again for at least 20 minutes. It appeared and disappeared in this pattern most of the night, working its way ever-so-slowly towards my car.

But the group of men made it to my car before the plow did. And they did their best to help me out. Most of the cars in front of us in the inner lane had now moved out. The cars to our right snaking across the drive had not. And the cars and buses had continued to pile up behind us.

The men tried to clear out around my car and then tried to push me back and forth, as I shifted between drive and reverse. The problem was that my left rear tire kept sliding back against the wall and I wasn’t getting enough traction to move forward. If one of them could have gotten back there to help the rear of the car from moving further into the packed snow I could have gotten out of there.

The constant shifting of gears put an undue strain on the car, and it just burned out. And the guys trying to help moved on to other cars.

I’ve always been asked why we didn’t get out of the car and walk over to Sheridan and Belmont. Good question. Neither I nor Jerral were dressed for the weather outside. Though we could see Sheridan Road far to our left, there was a huge park between us and Sheridan piled high with more than three feet of snow in some spots.

During this entire time I filed reports with TV and radio. I was on live with Steve and Johnnie on WGN Radio overnight trying to keep people up to date on what was happening, though nothing was happening. And then, unintentionally, I threw a scare into everyone.

When the car died, I couldn’t keep my phone charged. It was an old phone anyway and the battery didn’t hold power for long. I can’t remember if I had reported that the phone was dying out, but I heard later from many at the station and on Facebook that they thought I’d perished since they hadn’t heard from me for hours.

There was a knocking on the passenger side window not long after the car died. Jerral opened it up and a guy said something to the effect of “You’re Roger on WGN. If you want to get warm, come on back to our car.”

We decided to take him up on his offer. Unfortunately, we forgot to ask which car was his before he left us and went back to his car. We got out of our car and trudged a few feet before realizing we didn’t know which car the guy was in. We headed back to my frozen car, got inside, now wet and sweating and frozen and shaking.

We’d been sitting, wet, inside the frozen car for way too long, out of food and warmth. It was just after 4:00 a.m. Suddenly, along the southbound lanes, a CTA bus shows up. A police officer gets out and walks through the road divider towards our car and the others behind us. He tells us we need to abandon the car and get on the bus and we will be taken to a hospital.

Jerral gets out of his side and quickly moves to the waiting bus while I grab my computer/school bag from the rear seat, though the officer tells me to leave everything in the car. I’m glad I didn’t listen to him.

We struggled through the snow and over the road divider and made our way into the bus. It was as cold inside the bus as it was outside. There was no heat. We continued to pick up people. Many had no coats, gloves, or boots. The bus gets filled up and starts heading towards Advocate Illinois Masonic Hospital on Wellington.

I’m at the back of the bus, standing so others can sit, and two things happen—one very embarrassing. Mother Nature called again while I was on the bus—big time. I tried desperately to wait until I got to the hospital, but the pain was too much to bear.

I took out the empty drink container from my lunch bag and unscrewed the top. Under the cover of my winter jacket I aligned myself and met the call, so to speak. I covered the container and put it back in the lunch bag shortly before we arrived at the hospital.

Since the bus wasn’t heated, my wet feet inside my wet socks inside my wet shoes started to get colder and colder from standing on the cold floor of the cold bus. As we walked from the bus to the hospital, I found a bathroom in the hallway – as did many others. I poured out the contents of the container into a urinal and threw out the container.

We walked past tables in the cafeteria where they were taking our information and asking if we needed any medical assistance. The hospital had opened and stocked the cafeteria with lots of hot food, all free. There were ample amounts of coffee, hot chocolate, water, and other drinks. There were extra phones installed so people could call families and friends. There were extra computer stations installed. The hospital really went all out to take care of us, as several busloads had made their way there.

At the registration table, the second thing happened. I walked up to one of the hospital aides standing near the table and asked, “What does frostbite feel like? I don’t think I can feel my feet.”

The aide immediately got me in a wheelchair and rushed me to the emergency room. I remember wondering where Jerral was and concerned that I didn’t have time to let him know I was not going to be in the lunchroom with him.

In the emergency room, a nurse prepared a tray of lukewarm water, and I soaked my feet in it. While talking to the nurse, I found out her mother taught English and journalism at CVCA. Of course I knew her mother, and the nurse and I started talking up a storm. While we were talking, in walks Jerral.

After a while my feet started to gain some feeling. I don’t remember the exact time, but it was about 5:00 a.m. when I asked if I could use a phone to call the radio station. As I was being interviewed, I remember noticing some of the faces of the staff who suddenly realized I worked for a radio station.

While Jerral had bid goodbye and made his way home on the now-running CTA Red Line, I was scared. I didn’t want to get caught out in the cold again. I noticed a taxi or two leaving the hospital so I called for a cab—and waited for more than four hours before realizing one wasn’t coming.

It was now almost 11:00 a.m. I hadn’t been home for about 28 hours. The free food in the cafeteria was gone. The computers were shut down. I screwed up my courage and stopped feeling sorry for myself and headed across the street to the red line station. The sun was out now and I stood on the station platform facing west, the sun flooding over my face as I closed my eyes.

My clothes had dried out while at the hospital so I wasn’t worried about freezing again, though my toes were still tingling. Finally, a train came by and I got on board and headed to the Western Avenue stop on the Ravenswood. I got onto a Western Avenue bus headed north. Western had been plowed and traffic was moving, though light in volume.

The bus got to my stop about 1:30 p.m. and I was faced with dozens of my neighbors shoveling out the street and their cars covered in at least two feet of snow. I walked the block from the bus stop to where we lived and greeted Bridget and our dog, Rufus, with big hugs. A refreshing double espresso and something to eat preceded a long nap.

There was no school for a couple days as people tried to dig out from the storm and find their lost cars. Cars left on the Drive and other roadways during the storm had been cataloged and towed to several lakefront parking lots.

Our son came over and we used Bridget’s car to drive to the lots looking for my car. Not only did we check with the lot attendant and their computerized list, but we walked around the lots and checked on the city’s website for my car. There was no listing. It had disappeared.

I called into the station for a couple more interviews that day and night mentioning that the car was lost. The next morning I got a mysterious phone call—“Your car is at the corner of Halsted and Wolfram” CLICK!

I remember Steve and Johnnie telling me that someone from Streets and Sanitation department had contacted them the night I was stuck on the Drive asking where I was located. So maybe that’s who called me. Our then-son-in-law and I drove to the location and there was my car. The car had no snow on it, leading me to think that it got towed to an inside facility as opposed to one of the outside lots..

I got in the car, put the key in the ignition, turned it, and after a couple of seconds, it started up!! Amazing!! But my smile turned to a frown about three minutes later when the engine slowly sputtered and stopped. It wouldn’t start up again. And as we opened the hood, we saw why. The entire engine was frozen in a block of ice from top to bottom, left to right, front to back.

We called a service station near where we lived, Bee Zee, and they sent out a tow truck to pick us up. Our then-son-in-law drove back home while I rode with the truck driver back to the auto shop. The workers were amazed at what happened and took pictures of the frozen engine. Then they put the car on a rack and raised it as high as it could go to face a large heating unit hanging from the ceiling.

That’s where the car stayed while the ice melted away from the engine. I got a ride home, and the next day, the repair shop called to say the car was ready and in good working condition. They had to replace some parts but it was none the worse for the wear.

Three days after frostbite, a missing car, and a frozen engine, I was back on the road and working my regular shift at the radio station. What an experience.

Give Blood

Minutia Men

@MinutiaMen EP214 Florida, Flowers, and Filling Orders https://radiomisfits.com/mm214/

— Radio Misfits (@RadiosMisfits) January 31, 2021

Danny Bonaduce

The February issue of Illinois Entertainer is out and features my interview with Danny Bonaduce.