Quick question…is it Christmas yet? pic.twitter.com/0sWhGxgW5t

— Saturday Night Live - SNL (@nbcsnl) December 17, 2020

Musings, observations, and written works from the publisher of Eckhartz Press, the media critic for the Illinois Entertainer, co-host of Minutia Men, Minutia Men Celebrity Interview and Free Kicks, and the author of "The Loop Files", "Back in the D.D.R", "EveryCubEver", "The Living Wills", "$everance," "Father Knows Nothing," "The Radio Producer's Handbook," "Records Truly Is My Middle Name", and "Gruen Weiss Vor".

Friday, December 18, 2020

Almost Christmas

Melissa McGurren

Thursday, December 17, 2020

Free Kicks

#FreeKicks EP95: The Knives Are Out https://t.co/KkOLcA81Mg

— Rick Kaempfer (@RickKaempfer) December 17, 2020

Negro League Cubs

These Cubs also played in the Negro Leagues: Gene Baker, Ernie Banks, Monte Irvin, Sam Jones, and Luis Marquez. pic.twitter.com/j3LrN8EBFU

— Rick Kaempfer (@RickKaempfer) December 17, 2020

Succeeding Orion

From today's Robert Feder column--it looks like WGN has finally named a replacement for Orion Samuelson who will be retiring at the end of this month...

When the legendary Orion Samuelson retires at the end of the month after 60 years at WGN 720-AM, he’ll turn over the agribusiness beat to Steve Alexander, who’s been a news-and-business anchor and reporter at the Nexstar Media Group news/talk station since 2007. “Steve grew up on a farm and has the knowledge to know what is important to our audience of farmers, food producers and consumers,” Big O said of his successor. “I am delighted that he is available to continue the WGN tradition of serving this most important audience.” Alexander, who also co-wrote and published Samuleson’s 2012 autobiography, You Can’t Dream Big Enough, said: “When I’ve filled in for Orion over the past 12 years, I’ve often joked that he gave me the key to the tractor, and I was able to keep it out of the ditch until he returned. Come next month, I’ll try to keep the tractor upright and continue Orion’s efforts to explain how important agriculture is to all of us.”

Danny Bonaduce

What was Elvis like? How did it feel to box Donny Osmond? What about the day Danny got Jonathon Brandmeier to scream in fear? All of that is covered in our chat with this week's guest, my old Loop colleague Danny Bonaduce. https://t.co/e1JJCZaOHl

— Rick Kaempfer (@RickKaempfer) December 17, 2020

Wednesday, December 16, 2020

Satchel Paige

Now that the Negro Leagues have officially been re-classified as a Major League, this man's name is going to be all over the record books...

Satchel Paige on Pitching 160+ games in a row for 3 straight years. 👑 pic.twitter.com/6rfnsTqQws

— Rob Friedman (@PitchingNinja) December 16, 2020

Mugs Halas

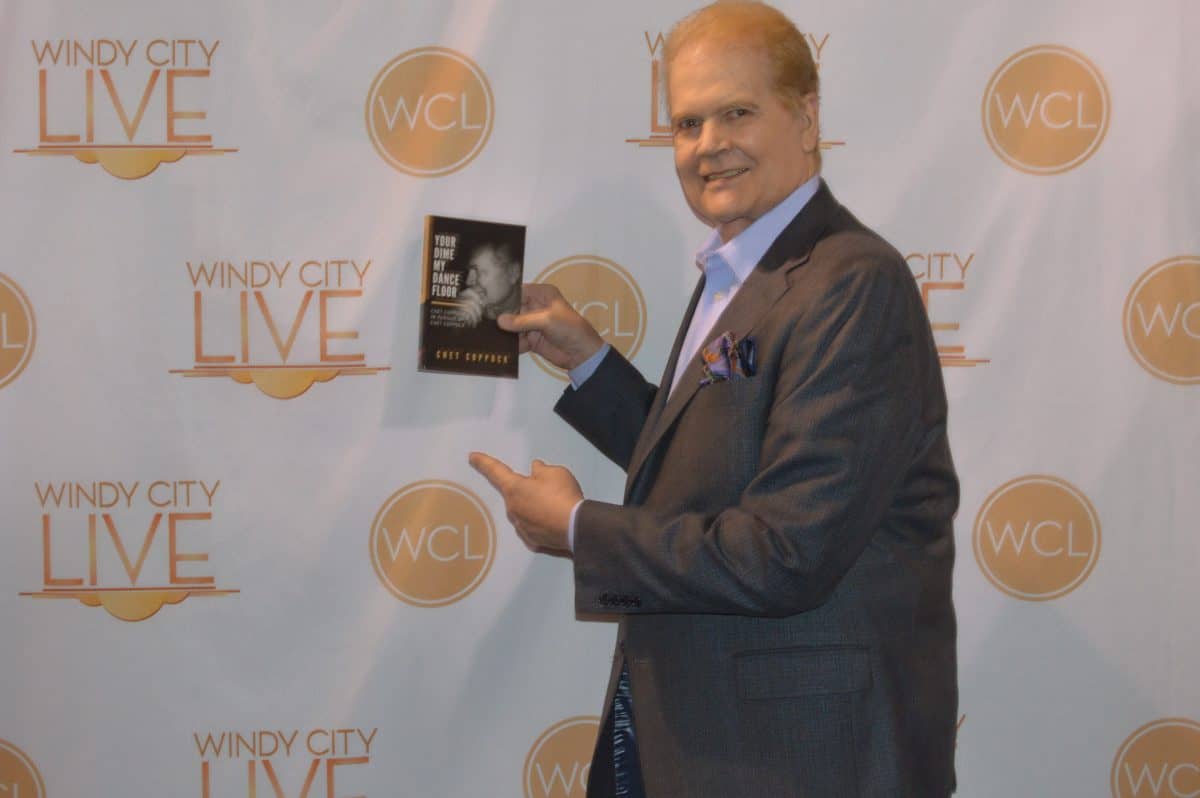

On this day in 1979, George Halas Jr. passed away. The son of the NFL Founder was a Bears executive too, but he died four years before his father. Eckhartz Press author Chet Coppock got to know the younger Halas (known as Mugs) and dedicated a chapter to him in his book “Your Dime, My Dance Floor”. We present it to you today as a free excerpt in honor of Mugs and Chet.

Remembering the Unknown Bear Heir: Mugs Halas

_____________

“Not every father gets a chance to start his son off in his own footsteps.”

Alan Ladd, motion picture star.

____________

The destiny of George Stanley Halas Jr. -“Mugs” to all who knew him -had already been determined before he emerged from the womb of his mom, Minnie Bushing “Min” Halas, on September 4, 1925.

The old man, George Halas, desperately wanted a son who would help him catapult the NFL past college grid, major league baseball, horse racing and boxing.

I’m not sure Mugs ever wanted the role he was assigned by default. Who knows?

The junior Halas remains the most elusive, unknown and, perhaps, misunderstood figure in Chicago sports history. Mugs had one curse he could not overcome. If it’s a son’s primary duty to please his father, Mugs was an AAA-list conscript.

Think about this: Halas, Jr. worked for the Bears for 29 years beginning in 1950. He was elevated to the role of club president in 1963, the same year the Papa Bear won his last NFL title as a head coach.

Yet Mugs never saw a camera or a note pad that he wouldn’t sprint across a state line to avoid.

I have just one recollection of seeing Mugs interviewed on television. It was before the Bears met Vince Lombardi and the Green Bay Packers the week of November 18, 1963. Some local reporter had managed to get the kid (nearing 40) in front of a camera to ask him about what was a critical Western Division showdown between his pop and Lombardi. The inquisitor simply asked Mugs to describe his thoughts about the upcoming battle (won by the Bears 26-7). Mugs, with absolutely no change of expression, simply said, “No predictions.”

Mugs made Jerry Krause look like Rodney Dangerfield. Yet, GSH, Jr., could be very likeable.

The brief TV answer no doubt pleased The Old Man. There is an odd conundrum which emerges between George Halas and his relationship with the press.

In the 1920s and 1930s, Halas begged for coverage. By the 1960s, the tough-edged Bohemian determined that the media had to be kept at a distance. There were times I felt The Old Man actually had a fear, a vibe of vulnerability about the press.

Ed Stone, a superb football writer for the Chicago American (later Chicago Today) was an expert on how Coach Halas operated. In 1963, he dared to criticize Halas for quitting on quarterback Bill Wade at half time of a ballgame against the 49ers at Kezar Stadium in San Francisco. Ed would pay for his Bear-knuckles honesty with his jaw. Halas simply called his drinking buddy Don Maxwell, the man who oversaw the Tribune and Today, and had Stone dropkicked off the beat.

Stone would be replaced by fresh-faced Brent Musburger, who had just recently graduated from Northwestern. (Musburger was years away from his current run as calling card of Vegas Stats and Info – vsin.com – with “his guys out in the desert.”)

The Bears were the last team in the NFL to send out “traditional” week-of-game press releases. Halas, as late as 1971, wouldn’t announce cuts during training camp. Why? The Halas public stance was he didn’t want the player embarrassed. Reality, it was just The Old Man playing games with the local press.

I’m not kidding when I tell you I saw beat writers in the late 1960s when the Bears were training in Rensselaer, Indiana, trying to count by hand who was still coming out for practice and who had been cut. The moves were so shadowy, just dripping with Howard Hughes meets Greta Garbo, that Stone once joking told me, “If the Bears had it their way they wouldn’t announce the schedule.”

Premier journalist Jeff Davis, who authored “Papa Bear: The life and legacy of George Halas” told me he has absolutely no recollection of Mugs ever being seen on TV, heard on radio, or quoted in a sports section or magazine. (Full disclosure: Jeff was my ace producer and insightful sounding board during my aborted run at WMAQ-TV.)

But what was the son to do? Mugs grew up during The Depression when the NFL was still getting scant coverage. By the time, he turned up on the old man’s payroll in 1950, the league was still a second tier, uncertain, red-haired stepchild in comparison to the college game.

Its primary ally was gambling. That hasn’t changed.

So, in his fifties as the name “George Halas” was becoming larger than life, what was Mugs to do? Did he really want to work for his dad? Would he have preferred to teach biology at a suburban high school?

Young Halas’s life was, at best, limited. He lived with his parents at 5555 N. Sheridan Road and attended Loyola University which was a driver and a nine-iron from the family residence.

Mugs wanted nothing more than to please the toughest of critics, his father, and in turn, show the public that he was not a guy to be messed with. Thus, Mugs, who could be the nicest guy on earth, elected to adopt a persona that was at once fierce and ornery. There undoubtedly was no crying at the Halas family dinner table.

Only a handful of people were allowed to see the socially comfortable Mugs Halas. One of those people was Bob Lorenz, who for years was the finest golfer you could find on the lush fairways of North Shore Country Club. Frankly, I just can’t think of anybody else who was that chummy with Mugs.

Young Halas did things that were nuts. Back in the 1960s, Mugs, outraged about an interception given up by Wade, kicked a hole in the wooden wall of the Bears old seasonal press box at Wrigley Field. His foot lived. The wall threw in the trowel.

This is one for the books: In 1977, when I was handling public address for the Bears, Mugs pulled me aside while we were both field level at Soldier Field.

“Coppock, come here,” Mugs barked. “Listen, Chet, I want you to stop using the phrase ‘preliminary signal.’”

I said sure, but asked Mugs what the issue was. He told me that “preliminary signal” was confusing the officials. Frankly, I was astonished. However, Mugs was just warming up. He added, “Most of these jerks are so bad they don’t know a yellow flag from their dicks.”

Amen. Mugs then asked how my mother was doing. Go figure.

Years earlier, when the Bears ousted Jim Dooley as head coach, Mugs came out of hiding to tell the press what a lousy and unfair job it was doing of covering his miserable football team. Halas, Jr. was not needed at this turkey shoot. In hindsight he was out there to show his dad, “Look, I can be as tough as you are…not tougher, dad…but, maybe just as tough.”

Mugs struggled all his life to carve his own identity. You’re the son of George Halas, no matter what you do, you’re just the old man’s kid who won big in the lucky sperm sweepstakes.

Does Mugs have a profound legacy with the Bears? Damn right, he does. In 1974, George, Jr., convinced his pop to let him pitch Jim Finks, who had built the Minnesota Vikings into a perennial NFL power, about bolting to Chicago to run the club with complete authority over every phase of the operation. Along with a small percentage of the team.

Honest to God, I don’t know – I would love to know – what Mugs said to his dad to convince him to stand down. It was a move that vaulted a woebegone franchise into the 20th century. Finks engineered the creation of Halas Hall in Lake Forest and ushered the Bears downtown offices from the sorrowful atmosphere at 173 W. Madison St. to dramatically upscale headquarters at 55 E. Jackson Boulevard.

Did I mention that Finks used his first draft pick as Big Bear to dice Walter Payton out of Jackson State (No. 4 overall in 1975)?

By this time, Mugs had found his niche. He became active in NFL affairs, winning league-wide respect for his ability to stabilize and upgrade one of the league’s most strategically important franchises.

*******

Muggs Halas died in the overnight hours of December 16, 1979. The move thrust Virginia McCaskey into a role she never thought she would occupy: principal owner of one of the NFL’s most storied teams.

Virginia is a wonderful woman but very much her father’s daughter. I’ve emceed three or four events Mrs. McCaskey attended and always enthusiastically introduced her as, “The NFL’s First Lady.”

The next time “The First Lady” says thanks for the buildup, I may keel over. I’ve only interviewed Virginia once and it was about as comfortable as an open-air midnight tea in Englewood.

Following a memorial service for Hall of Fame quarterback Sid Luckman in 1998, I dared to ask Virginia with microphone in hand to comment on her father’s favorite football-playing “son.” Mrs. McCaskey said about eight words. Yes, the old man would have been proud. Rachel Maddow could get more out of Melania Trump.

Now, let’s suppose Mugs had not passed away in 1979. He remains the club president and in turn I have no doubt he would have kept Jim Finks on the payroll for as long as Finks felt properly compensated, challenged and appreciated.

There is also no way in hell Mike Ditka would have ever coached the Bears.

Even in death, there were ominous clouds surrounding Mugs. His first wife Theresa, a lady that Halas, Sr. just couldn’t stand, began a money hunt. Terry and the McCaskeys were at war for years. In fact in 1987, she won the right to have her ex-husband’s body exhumed for an autopsy eight years after the man had died. If you can figure this one out you’re leaps and bounds ahead of me. During the autopsy it was revealed that virtually all of Mugs’ vital organs had been removed at death. His remains were on overload with saw dust.

What was the family trying to hide? By the mid-1980s Terry had sued the McCaskeys, Northwestern Memorial Hospital, the NFL and Pete Rozelle. (She left George Seals, Greg Latta and Brad Palmer out of the legal crossfire.) Was Terry thinking “double indemnity” or a bigger piece of a pie that had grown from perhaps $10,000,000 in 1970 to $400,000,000 in 1986?

George Halas was very much alive in 1979. Is there a Dealey Plaza/grassy knoll secret he was trying to hide? If the former Mrs. Halas won 50 cents it’s the best kept secret in the world. Much like Mugs, secrecy is the hallmark of the team that was guided by George Halas, misguided by Michael McCaskey, and now, follows the NFL herd rather than innovates under grandson George McCaskey.

The Old Man? He always left us guessing – from behind the curtain. Yet, I loved the Papa Bear and Mugs.

Melissa Leaves the Mix Morning Show

From Robert Feder's column this morning...

Melissa McGurren, the pride of Portage, Indiana, who rose from traffic reporter to full-fledged co-host of Eric Ferguson’s top-rated morning show, is out after more than two decades at WTMX 101.9-FM.

Officials of the Hubbard Radio hot adult-contemporary station ended speculation today about McGurren’s lengthy absence and announced a parting of the ways. She is expected to be paid through the end of the year, when her contract expires.

A statement released by the company alludes to a contract extension offer it says McGurren turned down, but it provided no other details.

I'm not going to speculate on what happened here other than to say it's not a simple contract dispute. I think this will be a big loss for the show.

I previously interviewed Melissa for Shore Magazine. You can read that here.

Tuesday, December 15, 2020

Ken Korber

Congrats to Eckhartz Press author Ken Korber for this piece in today's Daily Herald...https://t.co/OB7jJsssg7

— Rick Kaempfer (@RickKaempfer) December 15, 2020

Alan Freed

He coined the term “Rock and Roll” and yet few people remember the disc jockey Alan Freed. In his Eckhartz Press book “Turn it Up,” author Bob Shannon chronicles Freed’s contributions. On the 99th anniversary of Freed’s birth, we present this free excerpt from Shannon’s book…

Alan Freed: Mr. Rock ‘n’ Roll

Rock ‘n’ Roll was a verb, not a noun. In the beginning, more than almost 60 years ago, the words didn’t describe a type of music. Instead, in the black community, they were used as a euphemism for sex. In 1951, The Dominoes, with Clyde McPhatter singing lead, recorded Sixty Minute Man and, according to rock mythology, it was in the song’s suggestive lyrics that Freed first heard the words rock ‘n’ roll. What he did with them rocked the world.

Radio wasn’t Freed’s first love or even an early attraction, but he did have a jones for music.

He was born in Johnstown, PA in 1921 and, in 1933 his family moved to Salem, OH. It was during high school, in the mid ‘30s – when Benny Goodman’s band was hotter than a pistol – that Freed picked up the trombone and formed a combo he called The Sultans of Swing. From the start he saw himself as the band leader. He thought it a glamorous role and, onstage and off, he adopted a certain swagger that might have lasted years had it not been for an ear infection, which abruptly shattered his music making dreams. Bad news, yes, but the silver lining was it kept him out of the Army. (Freed’s 20th birthday was a week after the attack on Pearl Harbor).

In his late teens Freed traded his trombone for a microphone and, by 1946, when he hit 25, he’d already worked at WKST/New Castle, PA, and at WAKR/Akron – as an announcer, newsman and sportscaster – generally a jock of all trades.

At 28, Freed left Akron for the big city and a television job at WXEL-TV in Cleveland. He had nine years radio experience under his belt and had been hired to do a “disc jockey” show on TV. At the time, Freed wasn’t thinking about playing records on the tube; he thought that was a dead-duck approach and that’s exactly what he told the local paper. “I’d like to do away with records and depend entirely on live acts.”

But, it was television that got him noticed. “Friendliness makes more friends and that’s the ticket in television,” he said. (By the way, as a TV personality, Freed still spelled his first name with two “ls” and one “e” – Allen.) But, his fling with television was short lived and, in 1951, Freed returned to radio, when he landed a late night job playing classical music at WJW in Cleveland. In his book “The Fifties,” historian David Halberstam describes Freed as being “somewhat of a vagabond” and suggests that classical music was hardly Freed’s first love; this was just another way of saying the job was all about the money.

Then, along came record store owner Leo Mintz. Halberstam tells what happened this way: “Young white kids with more money than one might expect were coming into his store and buying what had been considered exclusively Negro music just a year or two before.”

What he means is that the lilywhite world of Cleveland, if not the entire United States, was about to be rocked on its axis.

Mintz convinced Freed that something new was happening and Freed agreed. The two men then convinced WJW management to give Freed a new show featuring this new music. Freed was jazzed about the idea and management was swayed by the money Mintz was willing to pay for sponsorship.

Freed decided to call the program “Moondog’s Rock ‘n’ Roll Party” and he proclaimed himself “The Moondog.”

On July 11, 1951 the show hit the air. In his new persona, Freed sided with the kids, professed his love for the music, and though he probably didn’t realize it, began to lead a revolution. “An entire generation of young white kids had been waiting for someone to catch up with them,” wrote Halberstam.

Nine months into the show’s run Freed decided he wanted to reward his loyal listeners – and, perhaps, put a little money in his pocket – so, he organized what (has since been identified as) the first live rock ‘n’ roll show, “The Moondog Coronation Ball.” He booked the top black acts in the country into the Cleveland Arena, a facility that held 10,000, and sold tickets for less than two dollars a piece.

Then, he held his breath.

On May 21, 1952 20,000 kids – white and black – showed up at the arena ready to party. The energy level was high and so was the body count, acerbated by hundreds of counterfeited tickets. It was, truly, a night to behold. The concert began. But, after only one song, fire authorities shut it down.

Still, a statement had been made: rock ‘n’ roll was here to stay. Freed, however, was getting itchy feet and while it didn’t happen overnight, within two years he left Cleveland and headed for New York City.

In the fall of 1954 Freed’s radio show debuted in New York on 1010/WINS and, within months, it was the #1 radio program in New York. WINS paid him $75,000 a year (about $450,000 in today’s dollars) and he added to his earnings by throwing live concerts at The Brooklyn Paramount.

The following year Hollywood caught on (to the discretionary money teenagers had to spend) and Freed, the Pied Piper, appeared in a series of low-budget rock ‘n’ roll movies, including “Don’t Knock The Rock,” “Rock Around The Clock” and “Rock, Rock, Rock.” Then, in 1957, The ABC Television Network gave Freed his own national TV show. Things began well enough, but when young Frankie Lymon (“Why Do Fools Fall In Love” – 1956) was seen dancing with a white girl, affiliates in the South went ballistic and the show was quickly cancelled.

This was the beginning of the end. The next year, WINS opted not to renew Freed’s contract. The reason, they said, was Freed’s indictment for inciting a riot at a Boston concert. Out at WINS, Freed crossed the street and joined competitor WABC. But, when he refused to sign a letter stating that he’d never accepted payola – he said it was a matter of principal – WABC fired him, too.

What happened to Freed next is essentially the tale of a career and a life in a tail-spin. Because he was so visible and so personified the music, a New York grand jury, convened in 1960 to look into irregularities in the record business, charged him with income tax evasion. (Before 1960, payola wasn’t illegal. But not reporting the payments as income was.) With no radio work to be found in New York, Freed moved to Los Angeles to work for KDAY, but the job didn’t last long and, dejected, he settled in Miami, where his career ended.

I could continue to focus this story on nasty little details that don’t paint a very positive picture of Mr. Freed, but I won’t, because they don’t matter. What does is that Alan Freed – in the face of a racially divided society – chose to play and champion rhythm and blues records. By doing so, he helped to usher in the dawn of the first rock age. No, he didn’t invent rock ‘n’ roll, but he was the first to use the term in the context we use it today.

There have been several movies made about Freed – most notably “American Hot Wax” and “Mr. Rock ‘n’ Roll” – but neither pays much attention to the facts and, from our perspective here in the 21st Century, that may be acceptable. Why? Because the spirit of Freed’s accomplishments transcend the details and he should be remembered, not for his failures, but for his successes and for what he did right.

In 1986, for his contributions to American culture, to rock ‘n’ roll and to the radio industry, Alan Freed was inducted into the Rock ‘n’ Roll Hall of Fame. It happened in Cleveland, where it all began, and as it should be.

Coming Soon

Good night Donald J. Trump... pic.twitter.com/27P9OxbPBW

— Rex Chapman🏇🏼 (@RexChapman) December 15, 2020

Monday, December 14, 2020

Minutia Men--Kangaroos, Kasper, and KFC

@MinutiaMen EP208 Kangaroos, Kasper, & KFC https://t.co/gVSEqODzKk

— Radio Misfits (@RadiosMisfits) December 13, 2020

Windy City Reviews: Signature Shoes

Book Review: Signature Shoes: The Athletes Who Wore Them and Delightful Pop Culture Nuggets

Signature Shoes: The Athletes Who Wore Them and Delightful Pop Culture Nuggets. Ryan Trembath, Eckhartz Press, November 28, 2020, Trade Paperback, 154 pages.

Reviewed by Brian R. Johnston.

As you’ve witnessed some of the greatest moments in sports history, have you ever wondered about the story behind the shoes that the athletes are wearing? If so, you’re in for a real treat, as Ryan Trembath has recently released his book, Signature Shoes: The Athletes Who Wore Them and Delightful Pop Culture Nuggets. I just completed the book and, as a big sports fan, I found it to be a fascinating read.

In the introduction, the author says, “The intentions of this book are to chronicle every signature shoe leading up to the Jordans and immediately following.” I would say that the author did a great job with this. The book is broken into many small chapters, each telling the story behind a signature shoe. It starts with a brief history of the origins of the idea of a signature shoe, followed by chapters on many different shoes that span the history of sports such as basketball, tennis, soccer, and others.

The author goes into a lot of detail describing each shoe, including what it looked like and why it was important in history. The majority of the book covers the 1970s, though there are also chapters from before then, as well as on the 1980s and 1990s. Mixed in with details about the shoes are entertaining explanations about pop culture trends that were taking place during the time each shoe was popular to place the shoes in historical context.

The book is easy to read, with clear language and without a lot of jargon that would make it difficult to understand. The author clearly has a passion for his topic, as it frequently shows throughout the book. In the middle, a section of photos shows the shoes he talks about

Whether you’re a fan of history, sports, collectibles, or all of the above, Signature Shoes would be an interesting read, and I recommend it to anyone who likes to study these topics.