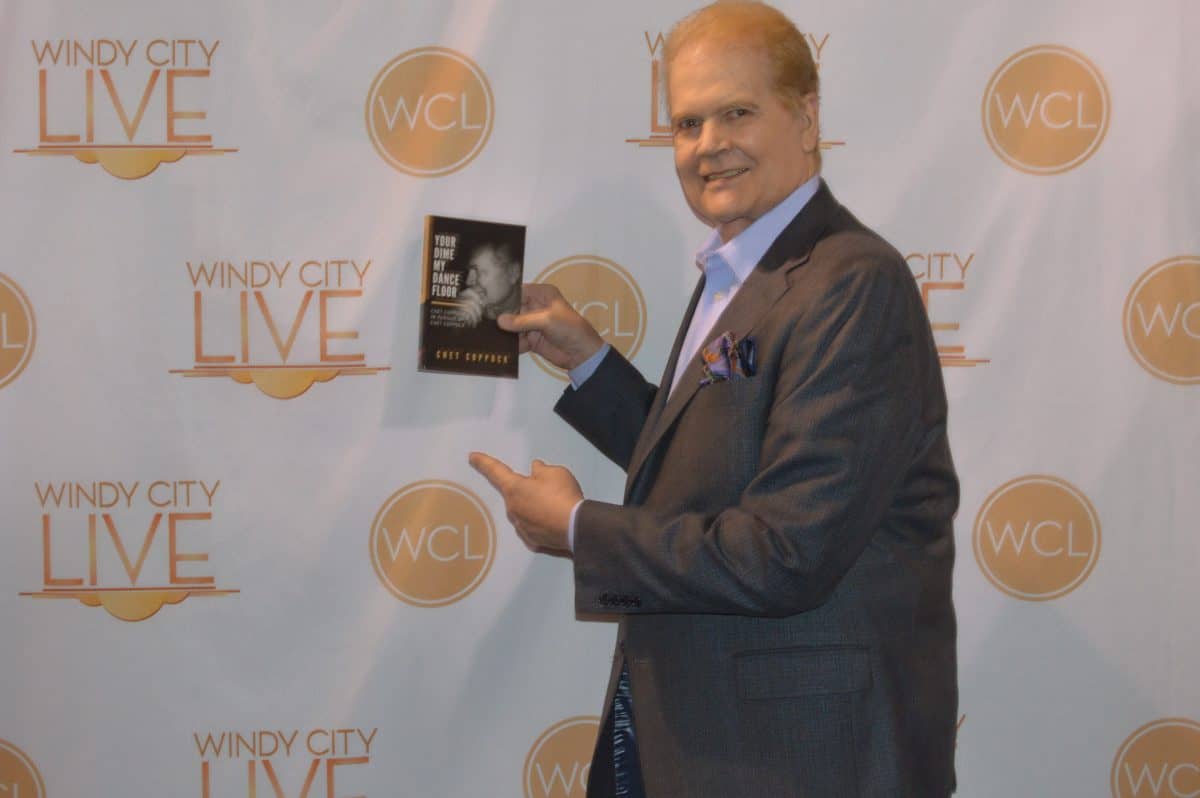

On this day in 1979, George Halas Jr. passed away. The son of the NFL Founder was a Bears executive too, but he died four years before his father. Eckhartz Press author Chet Coppock got to know the younger Halas (known as Mugs) and dedicated a chapter to him in his book “Your Dime, My Dance Floor”. We present it to you today as a free excerpt in honor of Mugs and Chet.

Remembering the Unknown Bear Heir: Mugs Halas

_____________

“Not every father gets a chance to start his son off in his own footsteps.”

Alan Ladd, motion picture star.

____________

The destiny of George Stanley Halas Jr. -“Mugs” to all who knew him -had already been determined before he emerged from the womb of his mom, Minnie Bushing “Min” Halas, on September 4, 1925.

The old man, George Halas, desperately wanted a son who would help him catapult the NFL past college grid, major league baseball, horse racing and boxing.

I’m not sure Mugs ever wanted the role he was assigned by default. Who knows?

The junior Halas remains the most elusive, unknown and, perhaps, misunderstood figure in Chicago sports history. Mugs had one curse he could not overcome. If it’s a son’s primary duty to please his father, Mugs was an AAA-list conscript.

Think about this: Halas, Jr. worked for the Bears for 29 years beginning in 1950. He was elevated to the role of club president in 1963, the same year the Papa Bear won his last NFL title as a head coach.

Yet Mugs never saw a camera or a note pad that he wouldn’t sprint across a state line to avoid.

I have just one recollection of seeing Mugs interviewed on television. It was before the Bears met Vince Lombardi and the Green Bay Packers the week of November 18, 1963. Some local reporter had managed to get the kid (nearing 40) in front of a camera to ask him about what was a critical Western Division showdown between his pop and Lombardi. The inquisitor simply asked Mugs to describe his thoughts about the upcoming battle (won by the Bears 26-7). Mugs, with absolutely no change of expression, simply said, “No predictions.”

Mugs made Jerry Krause look like Rodney Dangerfield. Yet, GSH, Jr., could be very likeable.

The brief TV answer no doubt pleased The Old Man. There is an odd conundrum which emerges between George Halas and his relationship with the press.

In the 1920s and 1930s, Halas begged for coverage. By the 1960s, the tough-edged Bohemian determined that the media had to be kept at a distance. There were times I felt The Old Man actually had a fear, a vibe of vulnerability about the press.

Ed Stone, a superb football writer for the Chicago American (later Chicago Today) was an expert on how Coach Halas operated. In 1963, he dared to criticize Halas for quitting on quarterback Bill Wade at half time of a ballgame against the 49ers at Kezar Stadium in San Francisco. Ed would pay for his Bear-knuckles honesty with his jaw. Halas simply called his drinking buddy Don Maxwell, the man who oversaw the Tribune and Today, and had Stone dropkicked off the beat.

Stone would be replaced by fresh-faced Brent Musburger, who had just recently graduated from Northwestern. (Musburger was years away from his current run as calling card of Vegas Stats and Info – vsin.com – with “his guys out in the desert.”)

The Bears were the last team in the NFL to send out “traditional” week-of-game press releases. Halas, as late as 1971, wouldn’t announce cuts during training camp. Why? The Halas public stance was he didn’t want the player embarrassed. Reality, it was just The Old Man playing games with the local press.

I’m not kidding when I tell you I saw beat writers in the late 1960s when the Bears were training in Rensselaer, Indiana, trying to count by hand who was still coming out for practice and who had been cut. The moves were so shadowy, just dripping with Howard Hughes meets Greta Garbo, that Stone once joking told me, “If the Bears had it their way they wouldn’t announce the schedule.”

Premier journalist Jeff Davis, who authored “Papa Bear: The life and legacy of George Halas” told me he has absolutely no recollection of Mugs ever being seen on TV, heard on radio, or quoted in a sports section or magazine. (Full disclosure: Jeff was my ace producer and insightful sounding board during my aborted run at WMAQ-TV.)

But what was the son to do? Mugs grew up during The Depression when the NFL was still getting scant coverage. By the time, he turned up on the old man’s payroll in 1950, the league was still a second tier, uncertain, red-haired stepchild in comparison to the college game.

Its primary ally was gambling. That hasn’t changed.

So, in his fifties as the name “George Halas” was becoming larger than life, what was Mugs to do? Did he really want to work for his dad? Would he have preferred to teach biology at a suburban high school?

Young Halas’s life was, at best, limited. He lived with his parents at 5555 N. Sheridan Road and attended Loyola University which was a driver and a nine-iron from the family residence.

Mugs wanted nothing more than to please the toughest of critics, his father, and in turn, show the public that he was not a guy to be messed with. Thus, Mugs, who could be the nicest guy on earth, elected to adopt a persona that was at once fierce and ornery. There undoubtedly was no crying at the Halas family dinner table.

Only a handful of people were allowed to see the socially comfortable Mugs Halas. One of those people was Bob Lorenz, who for years was the finest golfer you could find on the lush fairways of North Shore Country Club. Frankly, I just can’t think of anybody else who was that chummy with Mugs.

Young Halas did things that were nuts. Back in the 1960s, Mugs, outraged about an interception given up by Wade, kicked a hole in the wooden wall of the Bears old seasonal press box at Wrigley Field. His foot lived. The wall threw in the trowel.

This is one for the books: In 1977, when I was handling public address for the Bears, Mugs pulled me aside while we were both field level at Soldier Field.

“Coppock, come here,” Mugs barked. “Listen, Chet, I want you to stop using the phrase ‘preliminary signal.’”

I said sure, but asked Mugs what the issue was. He told me that “preliminary signal” was confusing the officials. Frankly, I was astonished. However, Mugs was just warming up. He added, “Most of these jerks are so bad they don’t know a yellow flag from their dicks.”

Amen. Mugs then asked how my mother was doing. Go figure.

Years earlier, when the Bears ousted Jim Dooley as head coach, Mugs came out of hiding to tell the press what a lousy and unfair job it was doing of covering his miserable football team. Halas, Jr. was not needed at this turkey shoot. In hindsight he was out there to show his dad, “Look, I can be as tough as you are…not tougher, dad…but, maybe just as tough.”

Mugs struggled all his life to carve his own identity. You’re the son of George Halas, no matter what you do, you’re just the old man’s kid who won big in the lucky sperm sweepstakes.

Does Mugs have a profound legacy with the Bears? Damn right, he does. In 1974, George, Jr., convinced his pop to let him pitch Jim Finks, who had built the Minnesota Vikings into a perennial NFL power, about bolting to Chicago to run the club with complete authority over every phase of the operation. Along with a small percentage of the team.

Honest to God, I don’t know – I would love to know – what Mugs said to his dad to convince him to stand down. It was a move that vaulted a woebegone franchise into the 20th century. Finks engineered the creation of Halas Hall in Lake Forest and ushered the Bears downtown offices from the sorrowful atmosphere at 173 W. Madison St. to dramatically upscale headquarters at 55 E. Jackson Boulevard.

Did I mention that Finks used his first draft pick as Big Bear to dice Walter Payton out of Jackson State (No. 4 overall in 1975)?

By this time, Mugs had found his niche. He became active in NFL affairs, winning league-wide respect for his ability to stabilize and upgrade one of the league’s most strategically important franchises.

*******

Muggs Halas died in the overnight hours of December 16, 1979. The move thrust Virginia McCaskey into a role she never thought she would occupy: principal owner of one of the NFL’s most storied teams.

Virginia is a wonderful woman but very much her father’s daughter. I’ve emceed three or four events Mrs. McCaskey attended and always enthusiastically introduced her as, “The NFL’s First Lady.”

The next time “The First Lady” says thanks for the buildup, I may keel over. I’ve only interviewed Virginia once and it was about as comfortable as an open-air midnight tea in Englewood.

Following a memorial service for Hall of Fame quarterback Sid Luckman in 1998, I dared to ask Virginia with microphone in hand to comment on her father’s favorite football-playing “son.” Mrs. McCaskey said about eight words. Yes, the old man would have been proud. Rachel Maddow could get more out of Melania Trump.

Now, let’s suppose Mugs had not passed away in 1979. He remains the club president and in turn I have no doubt he would have kept Jim Finks on the payroll for as long as Finks felt properly compensated, challenged and appreciated.

There is also no way in hell Mike Ditka would have ever coached the Bears.

Even in death, there were ominous clouds surrounding Mugs. His first wife Theresa, a lady that Halas, Sr. just couldn’t stand, began a money hunt. Terry and the McCaskeys were at war for years. In fact in 1987, she won the right to have her ex-husband’s body exhumed for an autopsy eight years after the man had died. If you can figure this one out you’re leaps and bounds ahead of me. During the autopsy it was revealed that virtually all of Mugs’ vital organs had been removed at death. His remains were on overload with saw dust.

What was the family trying to hide? By the mid-1980s Terry had sued the McCaskeys, Northwestern Memorial Hospital, the NFL and Pete Rozelle. (She left George Seals, Greg Latta and Brad Palmer out of the legal crossfire.) Was Terry thinking “double indemnity” or a bigger piece of a pie that had grown from perhaps $10,000,000 in 1970 to $400,000,000 in 1986?

George Halas was very much alive in 1979. Is there a Dealey Plaza/grassy knoll secret he was trying to hide? If the former Mrs. Halas won 50 cents it’s the best kept secret in the world. Much like Mugs, secrecy is the hallmark of the team that was guided by George Halas, misguided by Michael McCaskey, and now, follows the NFL herd rather than innovates under grandson George McCaskey.

The Old Man? He always left us guessing – from behind the curtain. Yet, I loved the Papa Bear and Mugs.