This year marks my 20th year as a professional writer. Over the course of 2024, I'll be sharing a few of those offerings you may have missed along the way.

Two days ago marked the 35th anniversary of my father's death. It was the single most impactful moment of my young life. I grew up overnight. My whole world view changed. I began to live every day like it could be my last.

These two stories about my dad may explain it. The first one appeared as the final essay in my book Father Knows Nothing.

Why do I write?

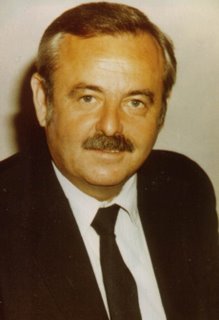

My Dad: Eckhard Kaempfer (1935-1989)

Losing a parent has a tendency to change your outlook on life. I know it happened to me. When my father died seventeen years ago, I was 25. That’s a pretty young age to become fatalistic, but I’ve chosen to look on the bright side of being fatalistic. For one thing, I no longer take things for granted because I know that my time on this earth is limited.

I know this is going to sound bad, but I wish my father had been a little more fatalistic. Of course, it’s totally unfair to say that about a man who walked into a hospital emergency room one day at the age of 54, and never came out again. His mindset was understandable. Both of his parents were still alive when he died. He had no reason to ever think about death. And even if he had, all three of his children were already adults (25, 24, and 19), and he had done a pretty good job of raising relatively normal functional members of society. Why would he bother thinking about what life would be like without him?

I know I’m being greedy here. I realize that. He gave me all he could give...and then some. But now that I’m a father myself, I find myself wanting something I never wanted before. His advice. I always considered Dad to be a source of wisdom, even when I strongly fought against it. He was a reasonable man, a thinker, someone who gave quite a bit of thought to his words before they came out. He wasn’t always right, but he was never rash or emotional. In short, he was the perfect kind of person to ask for advice.

And I never did.

And now that I’m a father myself, I have a million questions.

That’s probably one of the reasons I have so overcompensated with my own boys. I’ve tried to use my father as a model—his steady temperament and his guiding hand, while trying to give them what he couldn’t give me. It’s one of the reasons I’ve decided to stay home and raise them. I’m part of virtually every phase of their lives, and I’m constantly giving them unsolicited advice about every subject under the sun just in case they ever need it someday.

Unfortunately, I don’t quite have the fountain of wisdom my father had. He had knowledge that came from a difficult childhood of emigration and language barriers and hardship that I couldn’t even imagine. You learn things when you experience difficulty—and he must have learned so much. Most of those lessons learned, however, died with him. I didn’t have the foresight to ask about them, and he didn’t have the foresight to commit them to paper.

So I write.

That way, what I know will not go away when I go away. Even if my boys choose to ignore it for most of their lives, I’m fairly confident there will come a time when curiosity will get the best of them, and they will seek out wisdom from their father. When that time comes, there’s a possibility I won’t be around to deliver it in person.

The son spends his life trying to distance himself from his father, trying to make his own way in the world, trying to become a man. There’s nothing wrong with that—it’s part of growing up. I certainly don’t take it personally when my boys ignore my advice and insist on making the same mistakes I made. Some kids just learn better that way. I know I did. But there will come a day when they need me. And I just can’t bear to think that I won’t be there when they do.

So I write.

When they do seek me out, even if I’m not around, my words will still be here, to bring me back to life. They won’t have to wonder what was going through my mind when I was in their shoes--because they can read it. And if they end up having boys just like themselves—and my experience tells me they just might—they can see how and why I did what I did.

Why do I write? I know that part of the audience for every word I write includes three grown men I’ve never met. Three men who may one day want to ask Dad for advice. I only have my time, my love, and my words. I give those with all of my heart.

That’s why I write.

Losing a parent has a tendency to change your outlook on life. I know it happened to me. When my father died seventeen years ago, I was 25. That’s a pretty young age to become fatalistic, but I’ve chosen to look on the bright side of being fatalistic. For one thing, I no longer take things for granted because I know that my time on this earth is limited.

I know this is going to sound bad, but I wish my father had been a little more fatalistic. Of course, it’s totally unfair to say that about a man who walked into a hospital emergency room one day at the age of 54, and never came out again. His mindset was understandable. Both of his parents were still alive when he died. He had no reason to ever think about death. And even if he had, all three of his children were already adults (25, 24, and 19), and he had done a pretty good job of raising relatively normal functional members of society. Why would he bother thinking about what life would be like without him?

I know I’m being greedy here. I realize that. He gave me all he could give...and then some. But now that I’m a father myself, I find myself wanting something I never wanted before. His advice. I always considered Dad to be a source of wisdom, even when I strongly fought against it. He was a reasonable man, a thinker, someone who gave quite a bit of thought to his words before they came out. He wasn’t always right, but he was never rash or emotional. In short, he was the perfect kind of person to ask for advice.

And I never did.

And now that I’m a father myself, I have a million questions.

That’s probably one of the reasons I have so overcompensated with my own boys. I’ve tried to use my father as a model—his steady temperament and his guiding hand, while trying to give them what he couldn’t give me. It’s one of the reasons I’ve decided to stay home and raise them. I’m part of virtually every phase of their lives, and I’m constantly giving them unsolicited advice about every subject under the sun just in case they ever need it someday.

Unfortunately, I don’t quite have the fountain of wisdom my father had. He had knowledge that came from a difficult childhood of emigration and language barriers and hardship that I couldn’t even imagine. You learn things when you experience difficulty—and he must have learned so much. Most of those lessons learned, however, died with him. I didn’t have the foresight to ask about them, and he didn’t have the foresight to commit them to paper.

So I write.

That way, what I know will not go away when I go away. Even if my boys choose to ignore it for most of their lives, I’m fairly confident there will come a time when curiosity will get the best of them, and they will seek out wisdom from their father. When that time comes, there’s a possibility I won’t be around to deliver it in person.

The son spends his life trying to distance himself from his father, trying to make his own way in the world, trying to become a man. There’s nothing wrong with that—it’s part of growing up. I certainly don’t take it personally when my boys ignore my advice and insist on making the same mistakes I made. Some kids just learn better that way. I know I did. But there will come a day when they need me. And I just can’t bear to think that I won’t be there when they do.

So I write.

When they do seek me out, even if I’m not around, my words will still be here, to bring me back to life. They won’t have to wonder what was going through my mind when I was in their shoes--because they can read it. And if they end up having boys just like themselves—and my experience tells me they just might—they can see how and why I did what I did.

Why do I write? I know that part of the audience for every word I write includes three grown men I’ve never met. Three men who may one day want to ask Dad for advice. I only have my time, my love, and my words. I give those with all of my heart.

That’s why I write.

***

This was the piece I wrote about him on Father's Day in 2006...

Thank you Mary Ann Childers

I would like to take this opportunity to thank someone who often comes to mind when I think of my own father, especially on Father's Day: Mary Ann Childers.

Why do I think of the local Chicago news anchor when I think of my Dad?

It's a very odd story. I was the producer of the Steve and Garry show on WLUP, and we did a very special Christmas show one year--a full reading of the stage version of "A Christmas Carol" starring many local celebrities.

Among the celebrities present that day: Mary Ann Childers.

I don't remember what part Mary Ann played, but I remember that I cornered her backstage and asked her to do me a big favor. I told her that my father had a thing for her. He didn't say it was time to watch the news--he said it was time to watch Mary Ann. I asked if she would mind sending me an autographed picture of herself for Dad.

She seemed very flattered, but I really didn't expect her to do it. I figured she was a busy person and this was such a low priority that she probably wouldn't get around to it. That's probably why I was blown away when she sent me her promo picture with a personal note to my Dad saying... "It was a pleasure working with your son, Rick." The picture itself says "To Eckhard--Warmest Wishes for Christmas 1988. Mary Ann Childers."

I'll never forget how excited Dad was when he opened my present to him on Christmas Eve that year. I captured it on film...

Dad died six months later at the age of 54.

After he died I went to his office to clean out his things, and there she was, right in the middle of his desk: Mary Ann Childers. His co-workers told me that he joked with them about this picture all the time, saying that Mary Ann was his secret girlfriend.

Next Sunday is Father's Day. It's always a rough weekend for me. For the first twenty five years of my life, Father's Day weekend was a tribute to Dad. (And not just because it was Father's Day--it was his birthday too.) So, even now--seventeen years later, I struggle to enjoy Father's Day. I can't help thinking of Dad--and how much I miss him.

That's where Mary Ann Childers helps out.

When I don't want my sadness to ruin Father's Day for my kids, all I have to do is think of Mary Ann Childers. I remember how excited Dad was to get this picture from his "girlfriend," and it never fails to bring a smile to my face.

I've seen Mary Ann Childers a few times since Dad died--and I re-thanked her each time. Somehow I still don't think that's enough, so I'll say it again.

Thank You, Mary Ann.

One small gesture from you gave my Dad six months of enjoyment...and gave me seventeen years of comfort.

I'll never be able to repay you for that.

Why do I think of the local Chicago news anchor when I think of my Dad?

It's a very odd story. I was the producer of the Steve and Garry show on WLUP, and we did a very special Christmas show one year--a full reading of the stage version of "A Christmas Carol" starring many local celebrities.

Among the celebrities present that day: Mary Ann Childers.

I don't remember what part Mary Ann played, but I remember that I cornered her backstage and asked her to do me a big favor. I told her that my father had a thing for her. He didn't say it was time to watch the news--he said it was time to watch Mary Ann. I asked if she would mind sending me an autographed picture of herself for Dad.

She seemed very flattered, but I really didn't expect her to do it. I figured she was a busy person and this was such a low priority that she probably wouldn't get around to it. That's probably why I was blown away when she sent me her promo picture with a personal note to my Dad saying... "It was a pleasure working with your son, Rick." The picture itself says "To Eckhard--Warmest Wishes for Christmas 1988. Mary Ann Childers."

I'll never forget how excited Dad was when he opened my present to him on Christmas Eve that year. I captured it on film...

Dad died six months later at the age of 54.

After he died I went to his office to clean out his things, and there she was, right in the middle of his desk: Mary Ann Childers. His co-workers told me that he joked with them about this picture all the time, saying that Mary Ann was his secret girlfriend.

Next Sunday is Father's Day. It's always a rough weekend for me. For the first twenty five years of my life, Father's Day weekend was a tribute to Dad. (And not just because it was Father's Day--it was his birthday too.) So, even now--seventeen years later, I struggle to enjoy Father's Day. I can't help thinking of Dad--and how much I miss him.

That's where Mary Ann Childers helps out.

When I don't want my sadness to ruin Father's Day for my kids, all I have to do is think of Mary Ann Childers. I remember how excited Dad was to get this picture from his "girlfriend," and it never fails to bring a smile to my face.

I've seen Mary Ann Childers a few times since Dad died--and I re-thanked her each time. Somehow I still don't think that's enough, so I'll say it again.

Thank You, Mary Ann.

One small gesture from you gave my Dad six months of enjoyment...and gave me seventeen years of comfort.

I'll never be able to repay you for that.

A few more Cubs stories for you from this week in history...

July 7—Birthday of Billy Herman, Cub traded over drinks

July 8, 1947—All Star Game at Wrigley Field

July 8, 1890—Birthday of Rowdy Elliot, Unlucky Cub

July 9, 1885—Birthday of Buck Herzog, Cheating Cub

July 13, 1977—The NYC Blackout. Where were the Cubs?

July 13, 1995—The hottest day ever at Wrigley.